Gandon Editions

Works °8 — THE IRISH PAVILION (Brian Maguire and O’Donnell + Tuomey)

Works °8 — THE IRISH PAVILION (Brian Maguire and O’Donnell + Tuomey)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

group interview by Shane O’Toole; intro by Declan McGonagle

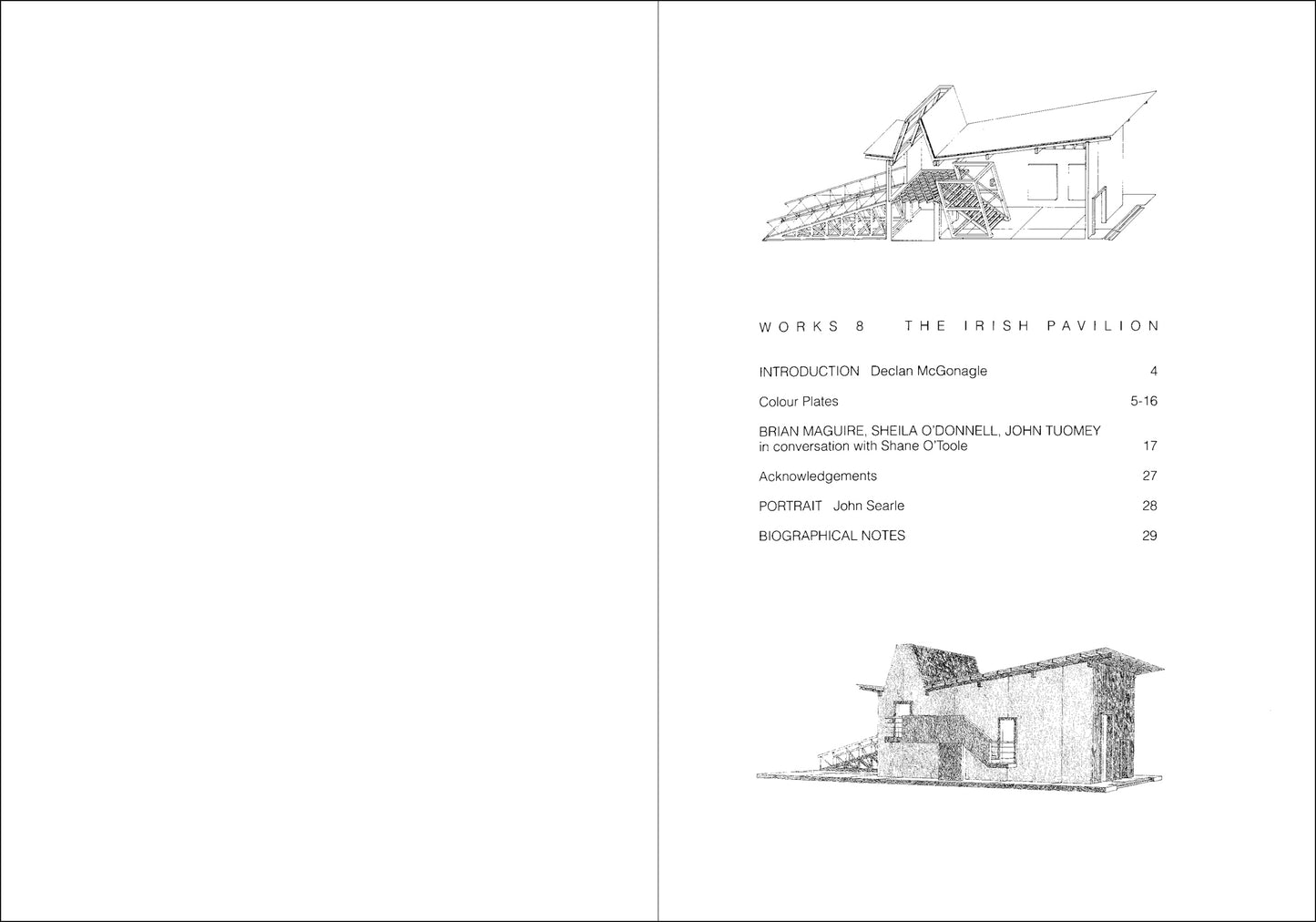

ISBN 978 0946641 253 32 pages (paperback) 20x15cm 19 illus

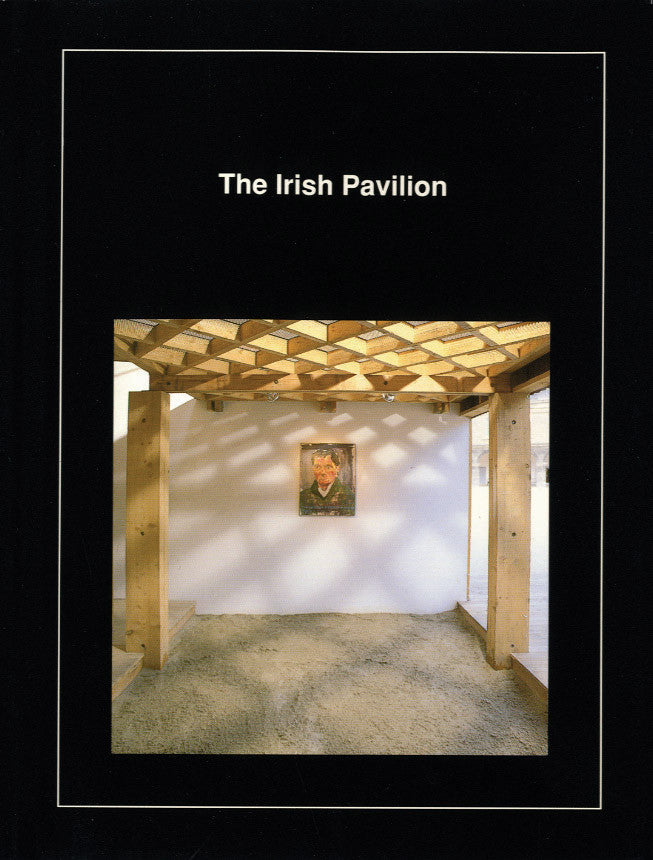

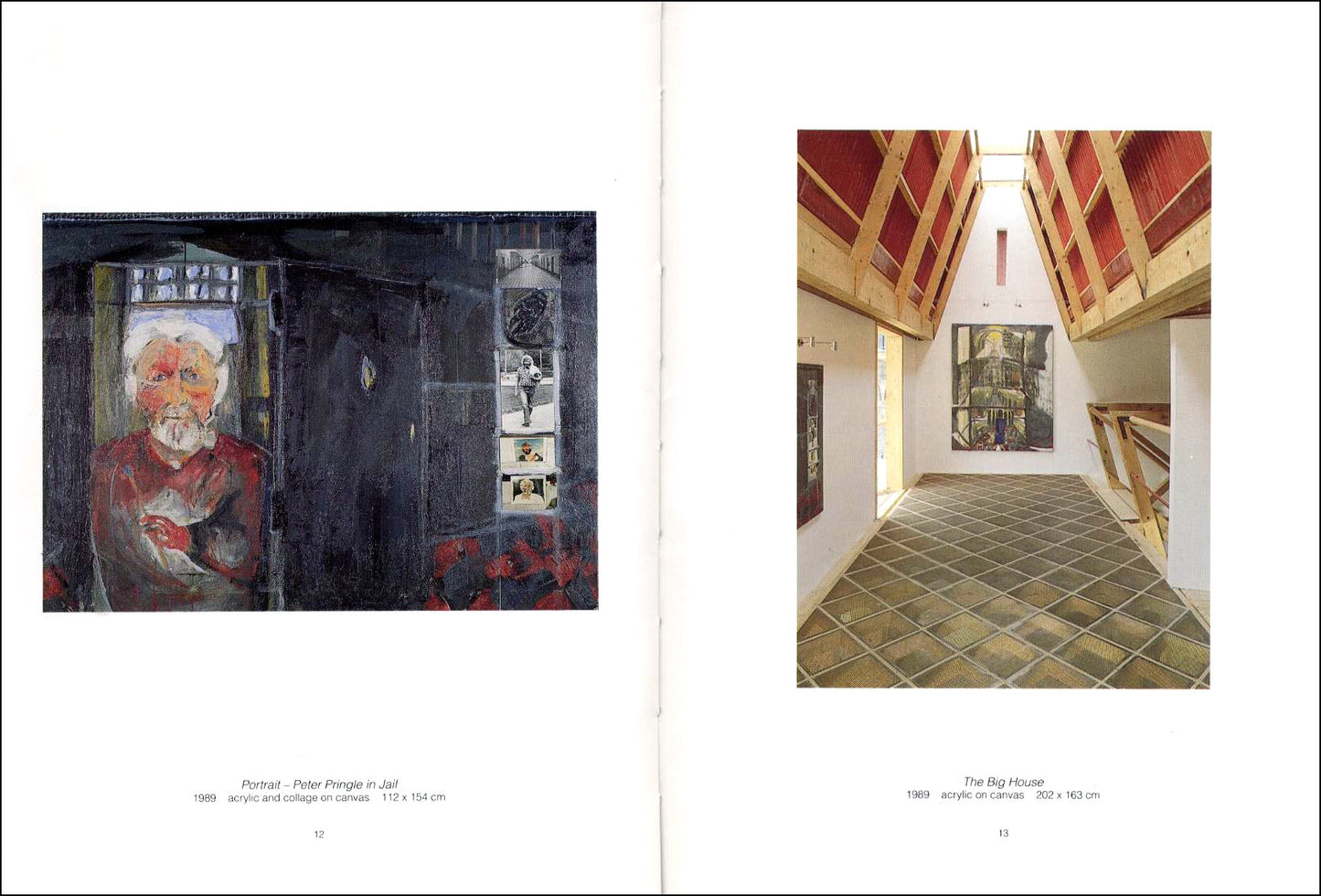

The Irish Pavilion addresses the social meanings and implications of art combined with architecture. Designed by architects Sheila O’Donnell and John Tuomey and sited in the grounds of the Irish Museum of Modern Art, the Pavilion housed an exhibition of striking paintings by the artist Brian Maguire. Much of the discussion in the book is about the relationship between the paintings and the space.

EXTRACTS

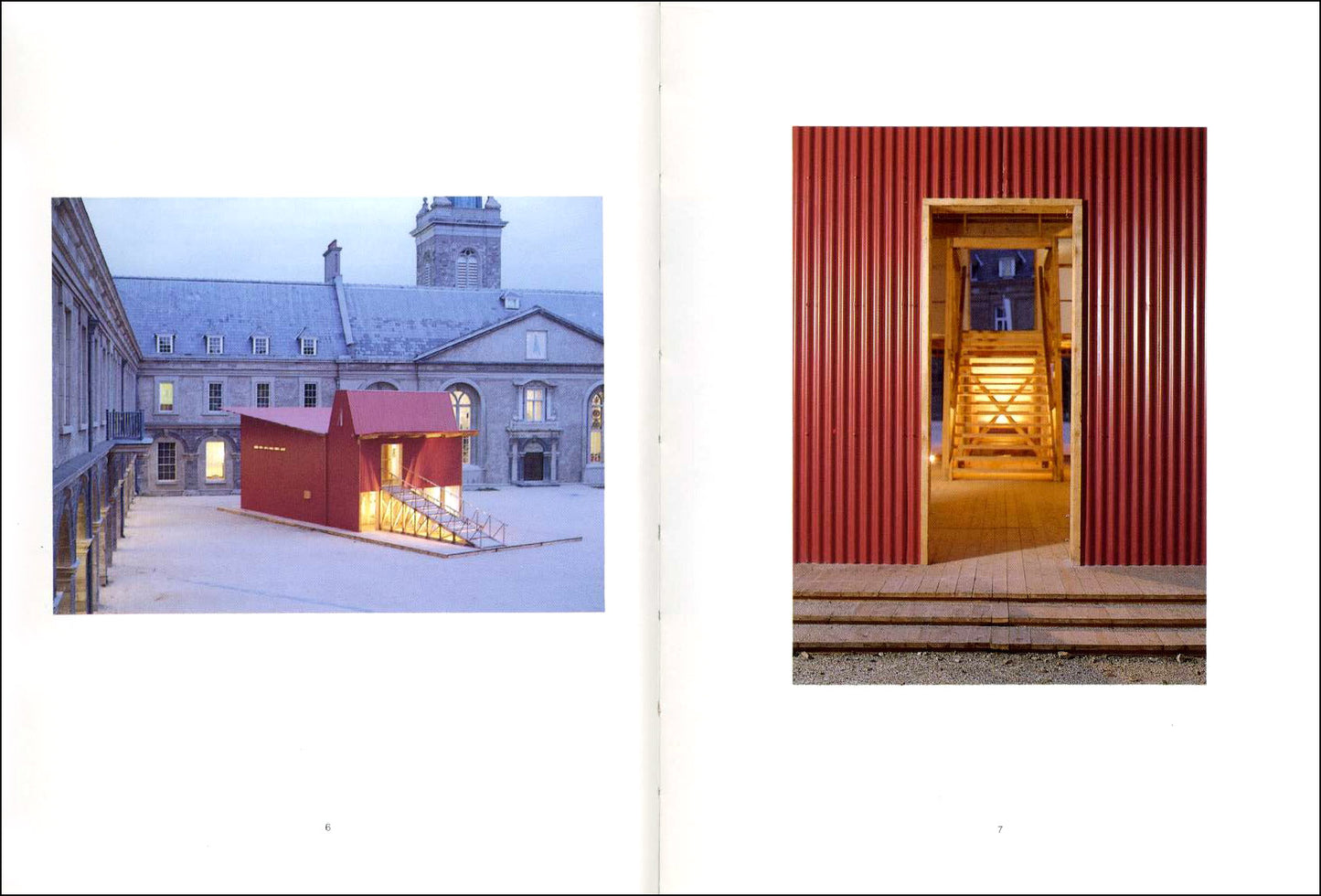

"The Pavilion was a building within a building, a gallery within a gallery, set askew within the symmetry of what is now, the first room in the Royal Hospital building, using vernacular forms and materials but actually taking its final form from the psychological space of the paintings by Brian Maguire. The series of paintings are essentially concerned with confinement and release, in prison, in love, and were echoed in the way the structure had to be entered and used. It had open and closed spaces, open and closed vistas. The Pavilion structure was created in direct response to meaning and not merely to the formal properties of the works. Externally, the red corrugated metal and unplaned timber provided a strong counterpoint to the Royal Hospital’s classicism. But this apparent discord was underpinned by a more fundamental continuity linking the basic social function of the Pavilion itself. Each describes and embodies human use and human value."

— from the introduction by Declan McGonagle

"BM – The pavilion is really the lost world behind the Victorian walls of our prisons. It is a hidden world. Actually, talking about it brings me back to the beginning of that Beckett book, The Lost Ones. It brings me back, in texture and in a sensual way, to the wings of Mountjoy Jail. I remember, at the outset, when we were talking about how we view the world, there seemed to be a difference in the way we each saw the city, or society or prison. Where I saw a dismal, grey reality – a stage for the repetitive struggle of life and death, or their lesser equivalents, with the greyness counterpointed by individuality and erotic expression – where the city is, in ways, akin to the architecture of the prison, you said something like, ‘If we saw the world the way you see it, or if we saw the city the way you see it, we wouldn’t be able to work.’ "

"SO’D – If you’re to survive within your own sense of yourself, working as an architect, you have to have some positive belief in the city as a place which can affect people’s lives in a way that isn’t negative. Or, that, as an architect, you can maybe make contributions to the city which actually enhance people’s lives. I think that’s why, although we found the prison paintings depressing, we could relate very strongly to those and understand this lost world you were talking about. Whereas, when we found your image of the city was as negative, that was harder for us to respond to. We’ve spent many years since we came back to Dublin working on projects for areas of the city which were derelict or neglected, making proposals for how they could be revitalised and repopulated. It was harder for us to relate to the non-prison work than to the prison work. The world of the prison was clearly a lost world, but the world of the city was something that we have a stake in."

"BM – I don’t attempt to make pictures out of a sense of hopelessness. The act of doing is an act of hope."

—from the interview with Shane O'Toole

|

CONTENTS Introduction by Declan McGonagle Liffey Suicides 1983 |