Crawford / Gandon

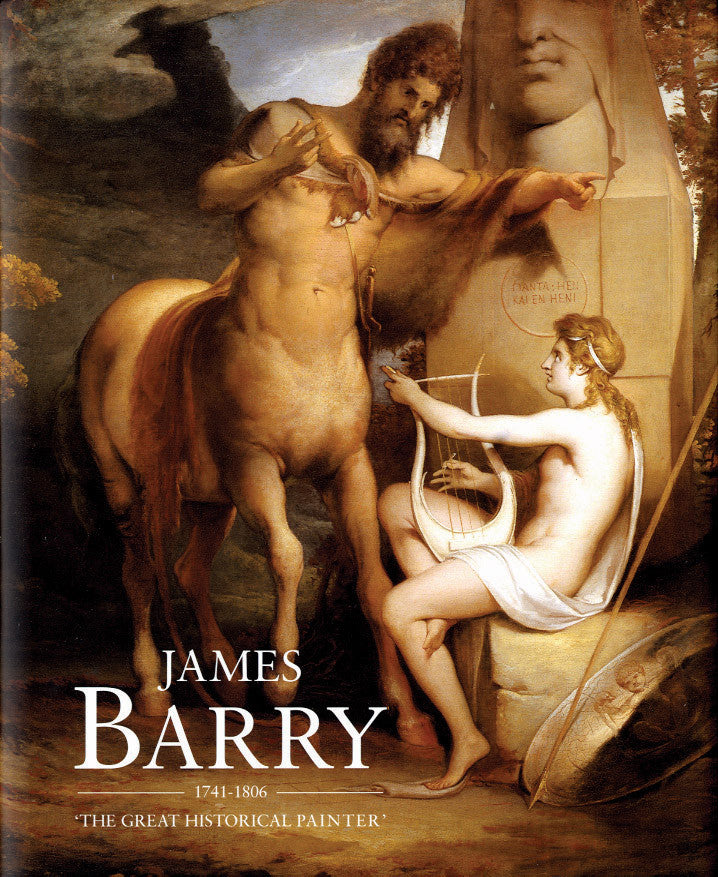

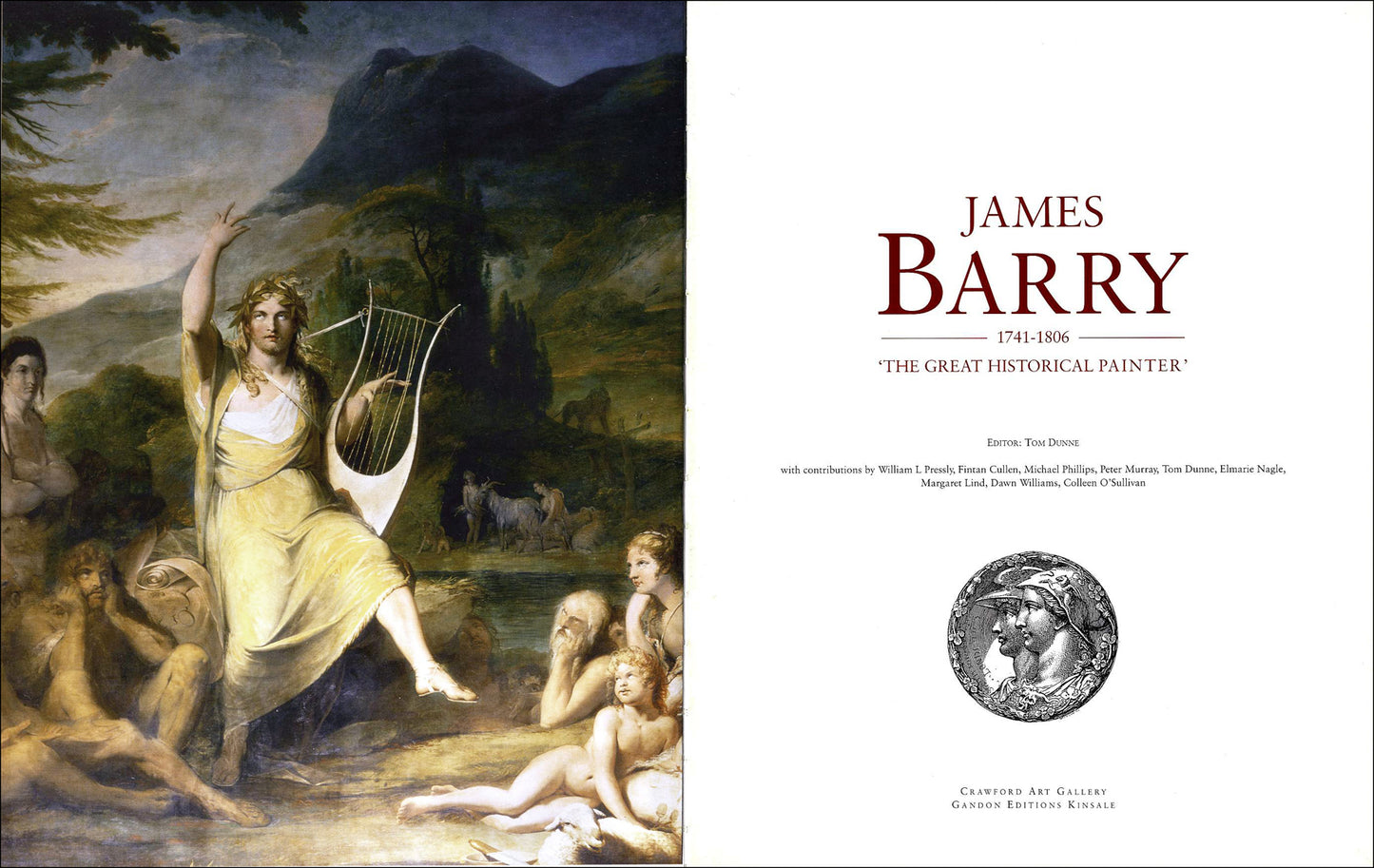

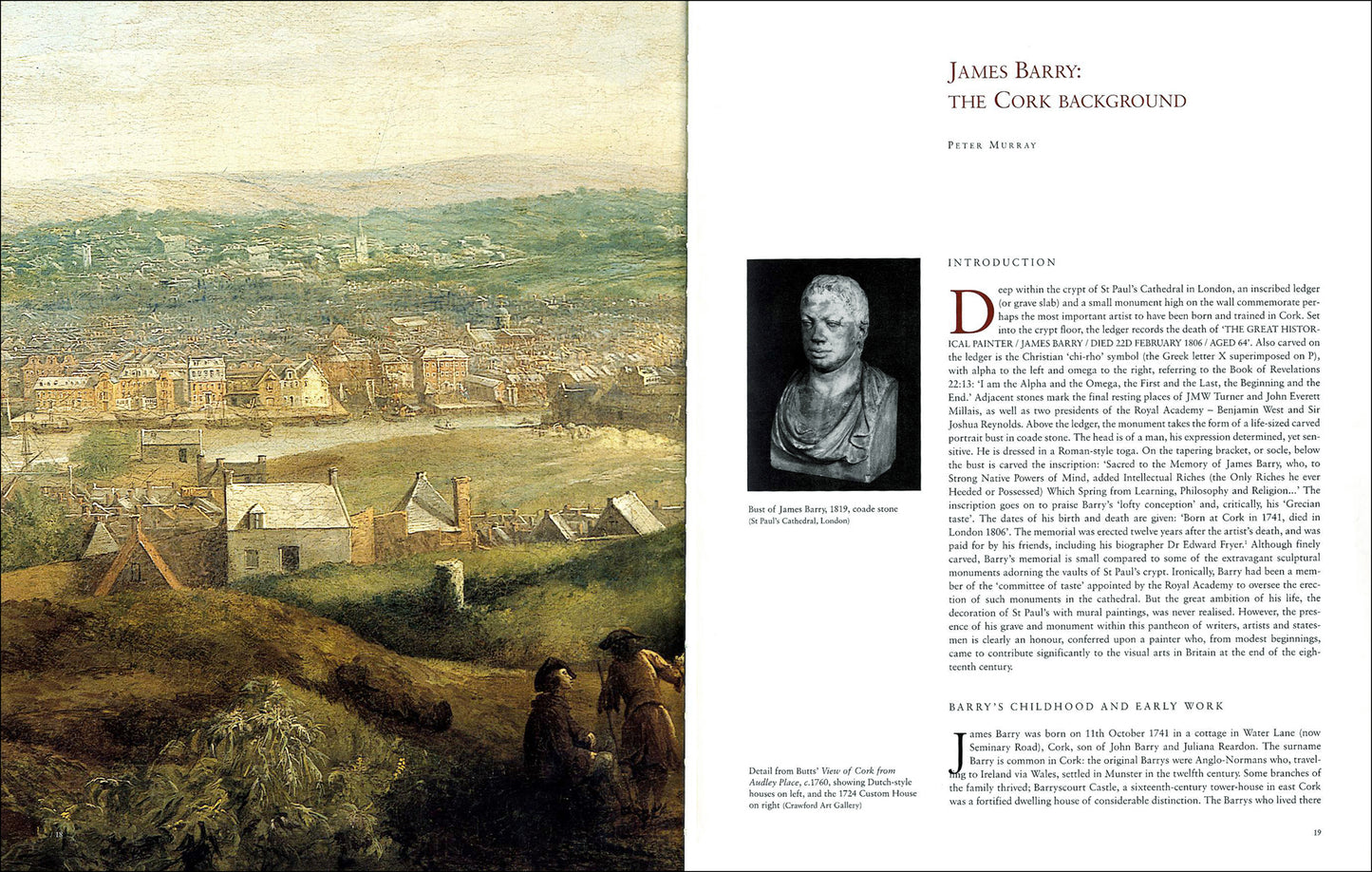

JAMES BARRY (1741-1806) — ‘The Great Historical Painter’

JAMES BARRY (1741-1806) — ‘The Great Historical Painter’

Couldn't load pickup availability

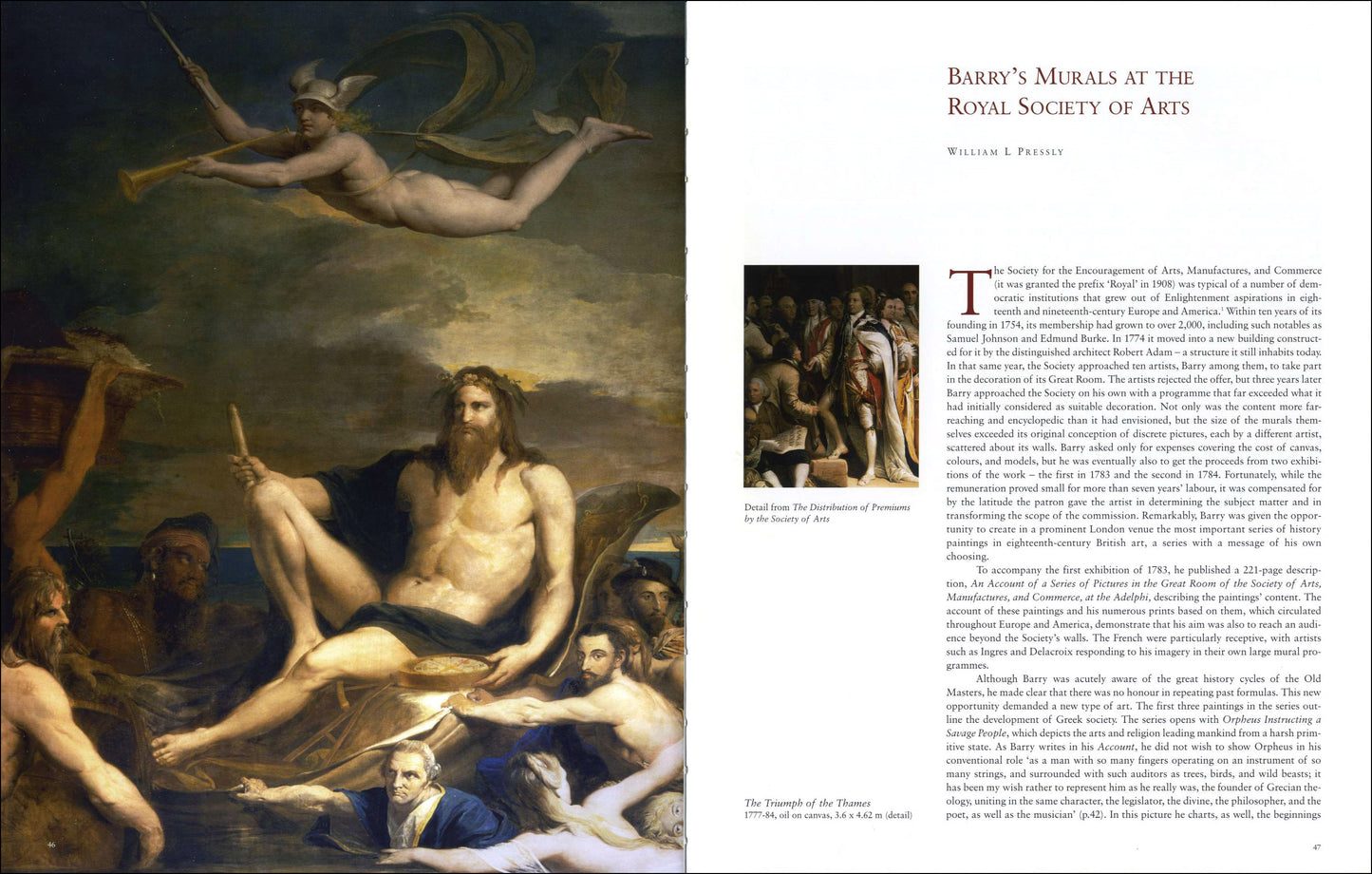

Share

ed. Tom Dunne

essays by Fintan Cullen, Tom Dunne, Peter Murray, Michael Phillips, William L Pressly

ISBN 978 0948037 252 224 pages (hardback) 30x24cm 234 illus index

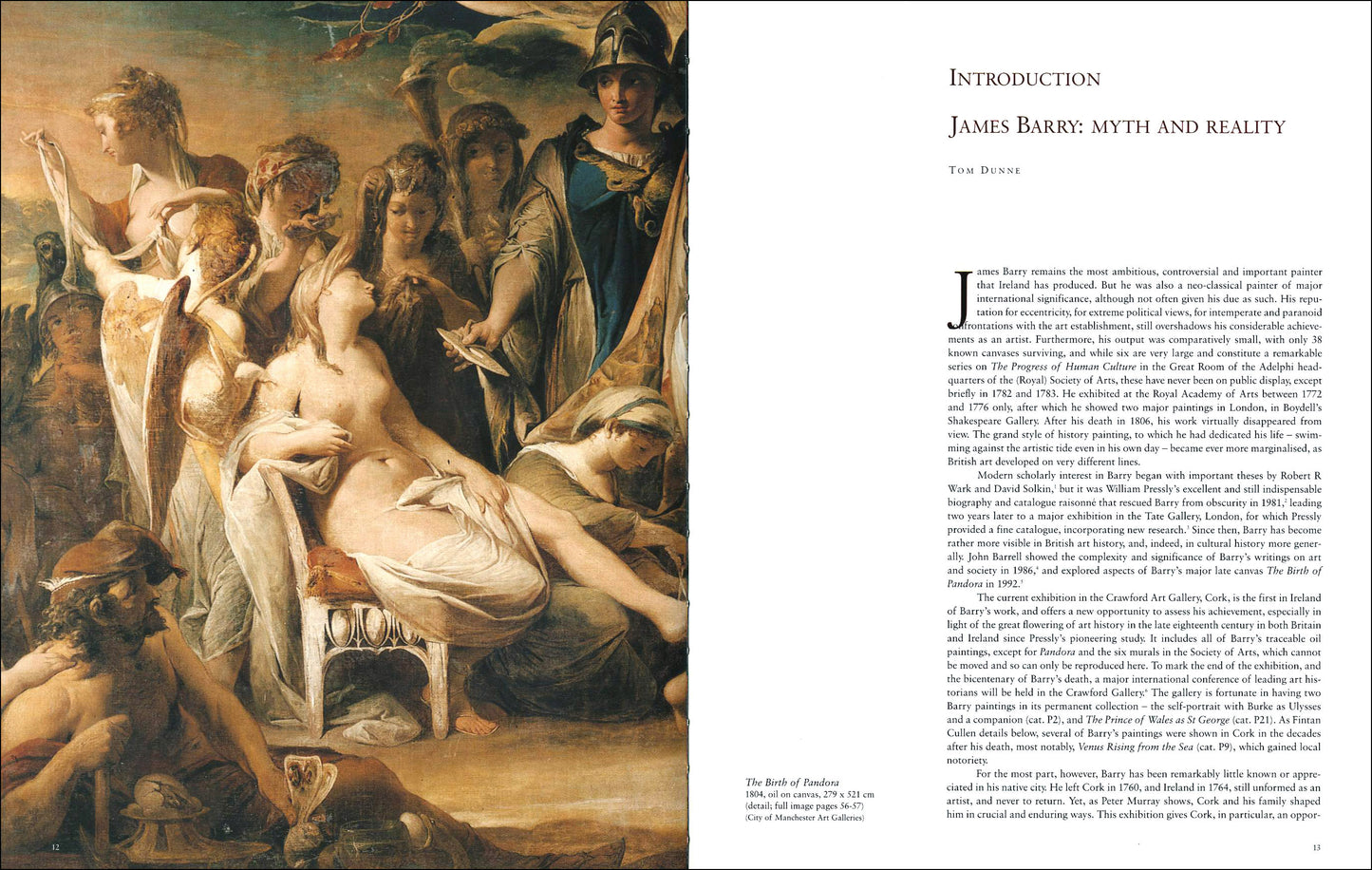

James Barry remains one of the most ambitious, controversial and important painters that Ireland has produced. But this Cork-born artist was also a neo-classical painter of major international significance, although not often given his due as such. His reputation for eccentricity, for extreme political views, for intemperate and paranoid confrontations with the art establishment, still overshadows his considerable achievements as an artist. Barry’s art aimed to be international and universal, grounded as it was not only in the Renaissance masters he most admired – Raphael, Michelangelo and Titian – but even more in classical Greek painting, long lost and known only from writings, and shadowed for him in Roman copies of Greek sculptures. For the most part, however, Barry has been remarkably little known or appreciated in his native city or country. This comprehensive and extremely handsome book gives the reader an opportunity to enjoy and understand better the work of one of Ireland’s greatest artists.

EXTRACT

"What James Barry later became was begun in Cork. The key aspects of his art – not least that extravagant imagination that met with such a cool reception in London – his love for Classical mythology, his critique of religion, his thirst for knowledge, his pride, sense of victimhood and brooding resentments, these can be traced back to his family history, and to the culture of mid-eighteenth-century Ireland. His training in London, Paris and Rome was largely in matters of technique and composition. Towards the end of his life, despite the enmity of many of his fellow Royal Academicians, Barry could yet look back on a lifetime of extraordinary achievement. As Ellis Waterhouse has pointed out, Barry’s art has ‘the spirit of a noble fire’, while his mural cycle, The Progress of Human Culture, in the Royal Society of Arts remains unique as the only project in which the theories of Sir Joshua Reynolds were realised.

Barry never lost the admiration of Henry Fuseli and William Blake, and was cheered by his students at the Royal Academy for his radical views. However, even in a recent history of British art, William Vaughan can assert that Barry has ‘sunk into oblivion outside specialist art historical circles’.1 That this could be the case, notwithstanding William Pressly’s ground-breaking 1983 exhibition at the Tate, seems extraordinary. In reviewing that exhibition, David Bindman described Barry as ‘an artist of true distinction, whose lofty ambitions were grounded in a real painterly sensibility and a natural mastery of monumental form’...

This publication builds on the existing scholarship of Robert Wark, David Solkin, William Pressly and David Allan, but includes new contributions by William Pressly, Tom Dunne, Fintan Cullen, Michael Phillips and Peter Murray. Practically all of Barry’s major paintings, apart from the murals in the RSA, which cannot be moved, have been brought together, along with hundreds of prints and drawings, to provide an opportunity of re-evaluating the contribution of this extraordinary painter of genius from Cork."

— from the foreword by Peter Murray

"Self-portraiture allows artists to fashion roles for themselves in which they can articulate a carefully crafted personal identity. In the second half of the eighteenth century, one frequently encounters self-portraits that establish the artist’s persona as a learned scholar, or as a gentleman of heightened sensitivity, or, with increasing frequency, as an inspired genius. Because Barry’s extravagant and daring paintings – works that are intended to challenge and provoke – are among the most original of his generation, it comes as no surprise that his self-portraits stand out from those of his contemporaries. Unlike the vast majority of his peers, he goes out of his way to evoke a strong reaction from the viewer, who, even at a glance, must acknowledge the direct intensity of his image or its often startling narrative elements. Barry places himself within complex structures where he becomes the artist-hero, acting out dangerous adventures such as fleeing a cannibalistic giant or enduring the hissing of a wrathful serpent. His statement – ‘It should be permitted only to a hero to commemorate a hero’ – literally comes true in these works. His determined association with the classical past also allows him to participate in an ongoing dialogue with how he measures up to the revered ancient Greek masters. His is an aggressively masculine and aggrandising vision of self, but, intriguingly, a contemporary who comes close to him in self-presentation within an elaborate mythic allegory is Angelica Kauffmann in her Self-Portrait between the Arts of Music and Painting (Pushkin Museum, Moscow), a work she conceived and executed in Rome in the early 1790s.

Barry also breathes new life into a convention that goes back to the Renaissance, in which the artist sees himself as a Christ-like figure, a god-like creator who suffers for his original insights. In his self-fashioning, the roles of the artist as classical hero and as Christ-like creator are intimately intertwined ... In regards to the question posed in this essay’s subtitle: ‘Who’s afraid of the Ancients?’, one answer would be, at least for a time, James Barry. At the beginning of his career, he had set himself the daunting task of competing with his revered predecessors, but by the end he could at last depict himself as their equal. No longer a pygmy standing on the shoulders of giants, he had become a giant himself.

But there was a high price to pay for greatness: the greater the man, the more envy he inspires and the more he becomes a target from which only death can release him. Barry’s genius is what has put him at risk, and in this context his closest identification is with the greatest of the ancients, Christ himself, who was murdered because of his palpable superiority. The Greeks had their own famous response to an insidious attack on a great man in the allegorical work The Calumny of Apelles, but the Crucifixion provides a considerably more sobering outcome and moral. Barry’s identification with the Saviour in the tradition of imitatio Christi (the imitation of Christ) placed on him an enormous burden. Given his perception of genius’s relationship to the larger culture, he had ample reason throughout his career for fear and trembling."

— from the essay by William L Pressly

|

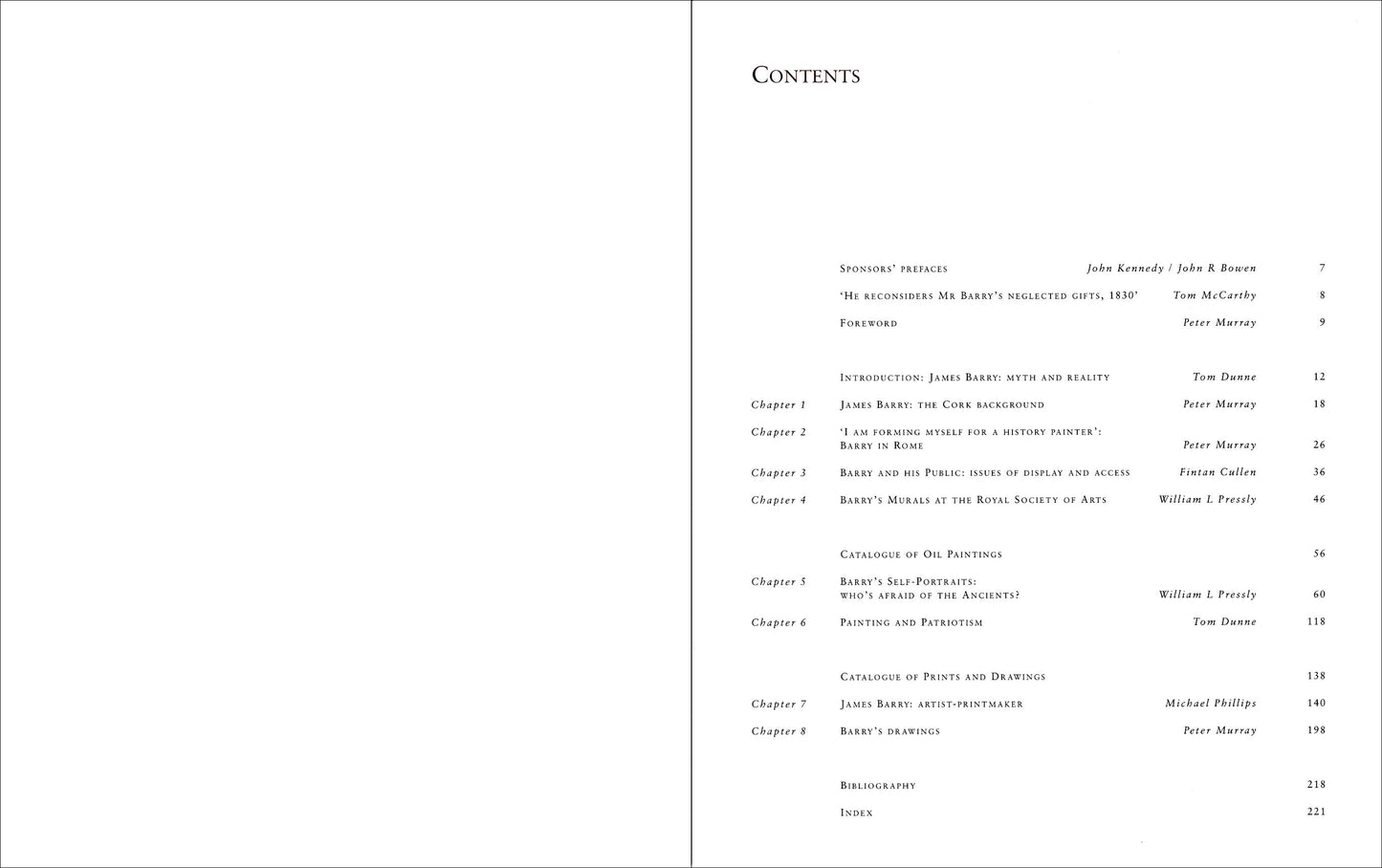

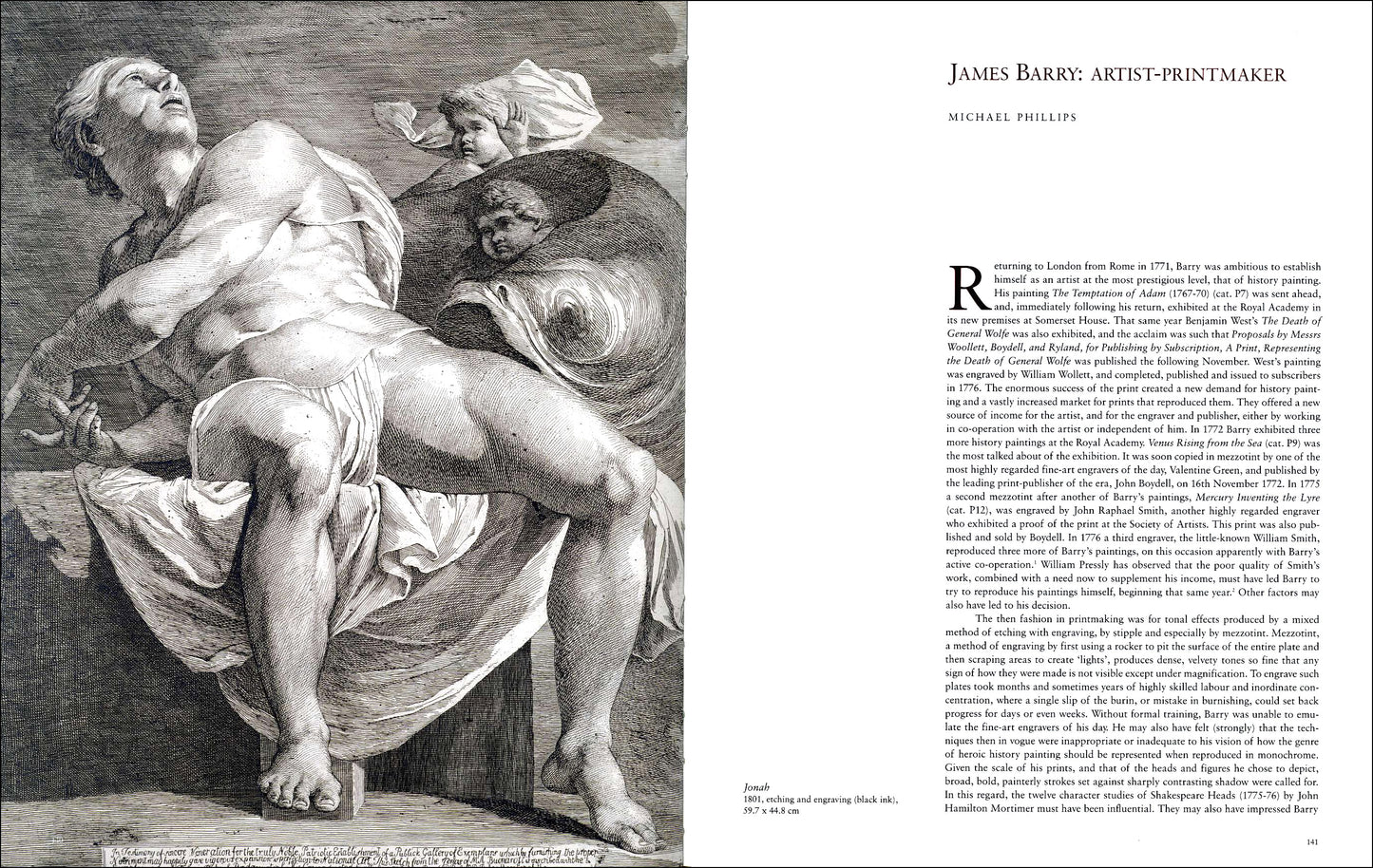

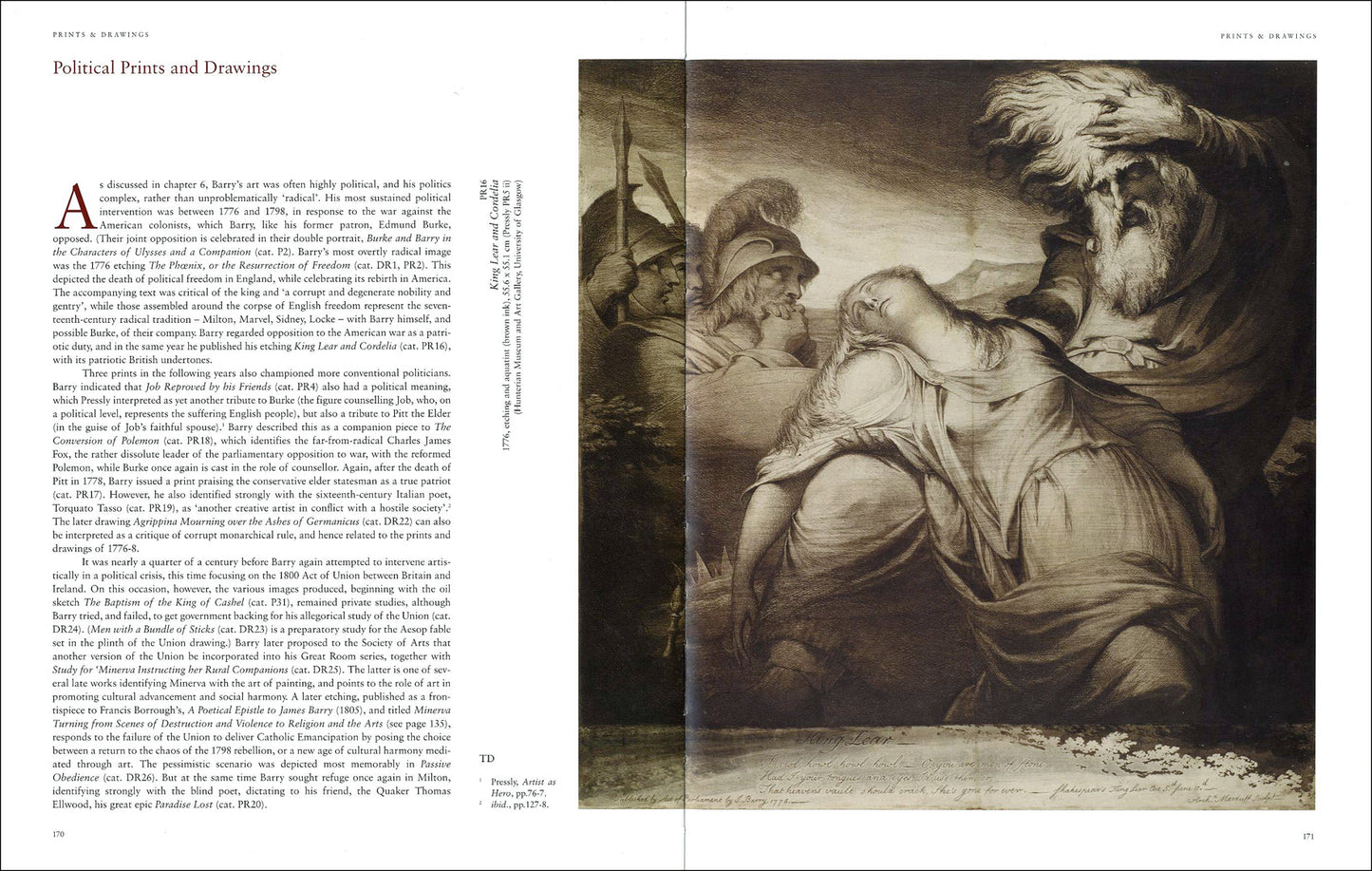

CONTENTS Sponsors’ prefaces by John Kennedy / John R Bowen 7 CHAPTER 1 – James Barry: the Cork background by Peter Murray 18 CHAPTER 2 – ‘I am forming myself for a history painter’: Barry in Rome by Peter Murray 26 CHAPTER 3 – Barry and his Public: issues of display and access by Fintan Cullen 36 CHAPTER 4 – Barry’s Murals at the Royal Society of Arts by William L Pressly 46 CATALOGUE OF OIL PAINTINGS 56 CHAPTER 5 – Barry’s Self-Portraits: who’s afraid of the Ancients? by William L Pressly 60 CHAPTER 6 – Painting and Patriotism by Tom Dunne 118 CATALOGUE OF PRINTS AND DRAWINGS 138 CHAPTER 7 – James Barry: artist-printmaker by Michael Phillips 140 CHAPTER 8: Barry’s drawings by Peter Murray 198 Bibliography / Index (incl. list of illustrations) |