Barryscourt Trust / Gandon Editions

Barryscourt Lectures 3 — TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE IN ANGLO-NORMAN MUNSTER

Barryscourt Lectures 3 — TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE IN ANGLO-NORMAN MUNSTER

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

by Colin Rynne

ISBN 978 0946641 840 32pp (pb) 24x17cm 10 illus

The Anglo-Norman period in Munster can be characterised as one of remarkable economic growth. Agricultural development was advanced enough to enable the widespread use of water-powered grain mills amongst all levels of early Irish society. On the basis of the archaeological evidence for the use of water power before the Anglo-Norman settlement, Ireland could not be considered a technological backwater in the early medieval period. Yet, while Anglo-Norman settlers would have found that the native Irish were accomplished millwrights, they had their own distinctive contribution to make, laying, as they did, the seeds of future industrial development in Ireland.

In this book, the author outlines the extent of Anglo-Norman settlers’ contribution to the development of industrial energy in Ireland, with special reference to the Munster area. A glossary of technical terms is provided in an appendix.

Continuing the excellent series of booklets from the Barryscourt Trust, we have here a clearly written, well-researched and beautifully illustrated paper by one of Ireland’s foremost authorities on medieval and post-medieval technology and industry ... The scholar, student and interested reader alike will find this book both informative and accessible.

— Maurice F Hurley, Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society

The third lecture, by Colin Rynne, is a fine study based on the author’s own extensive research.

— Irish Historical Studies

_____

EXTRACT

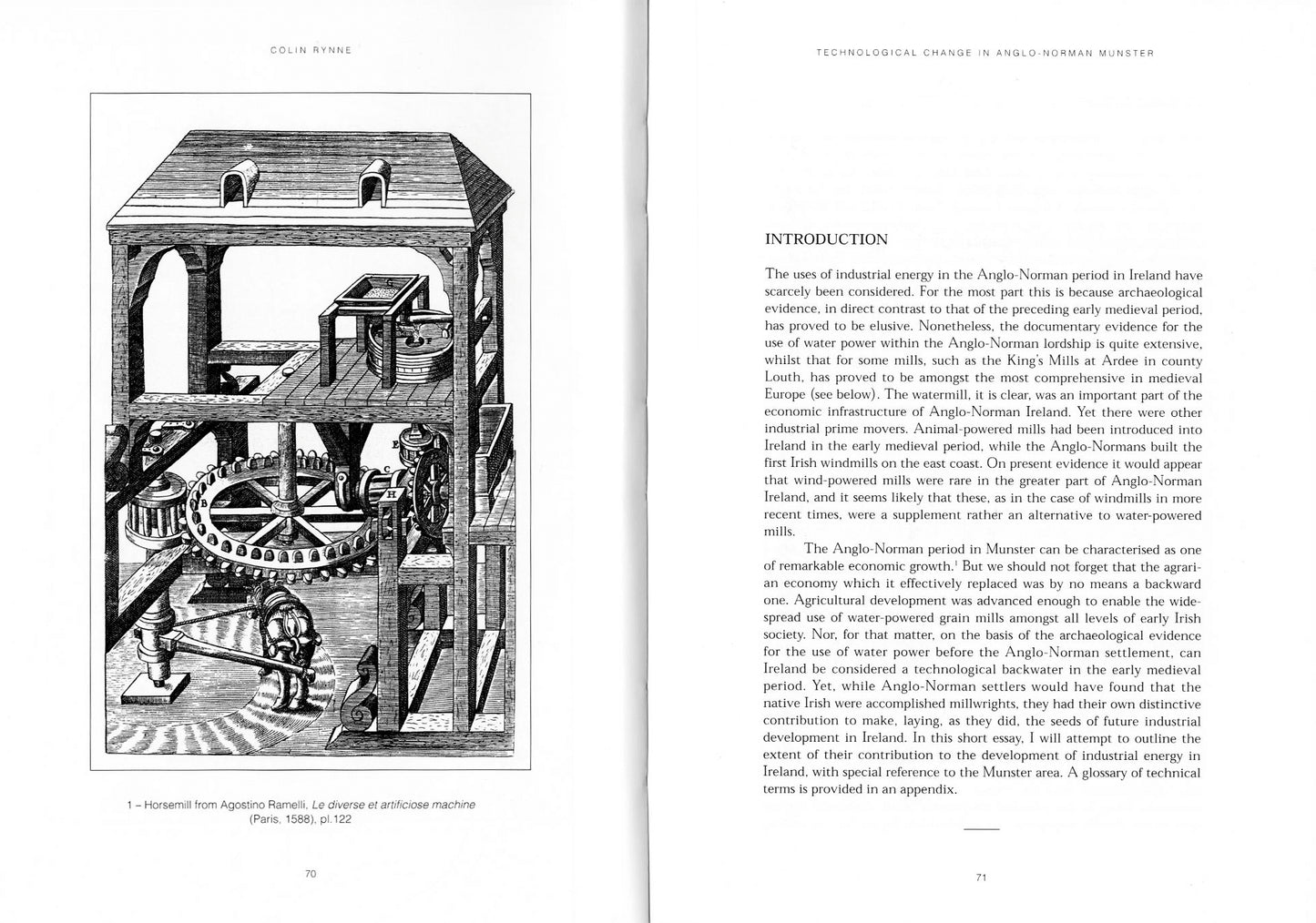

"The introduction of the wind-powered mill into Ireland is unquestionably an Anglo-Norman development, although the first recorded instance of such a mill occurs almost one hundred years after the first recorded English windmill of 1185. The earliest documented windmill in Ireland was at work at Kilscanlan, near Old Ross, county Wexford, in AD 1281. This is most likely to have been a post mill, in which the actual mill building is rotated about a central wooden pivot in order that the wind sails can face into the prevailing wind. The entire structure could be rotated through 360 degrees by means of a tail pole, which enabled the miller to adjust the position of his sails to accommodate changes in wind direction, by the simple expedient of rotating the entire mill building.

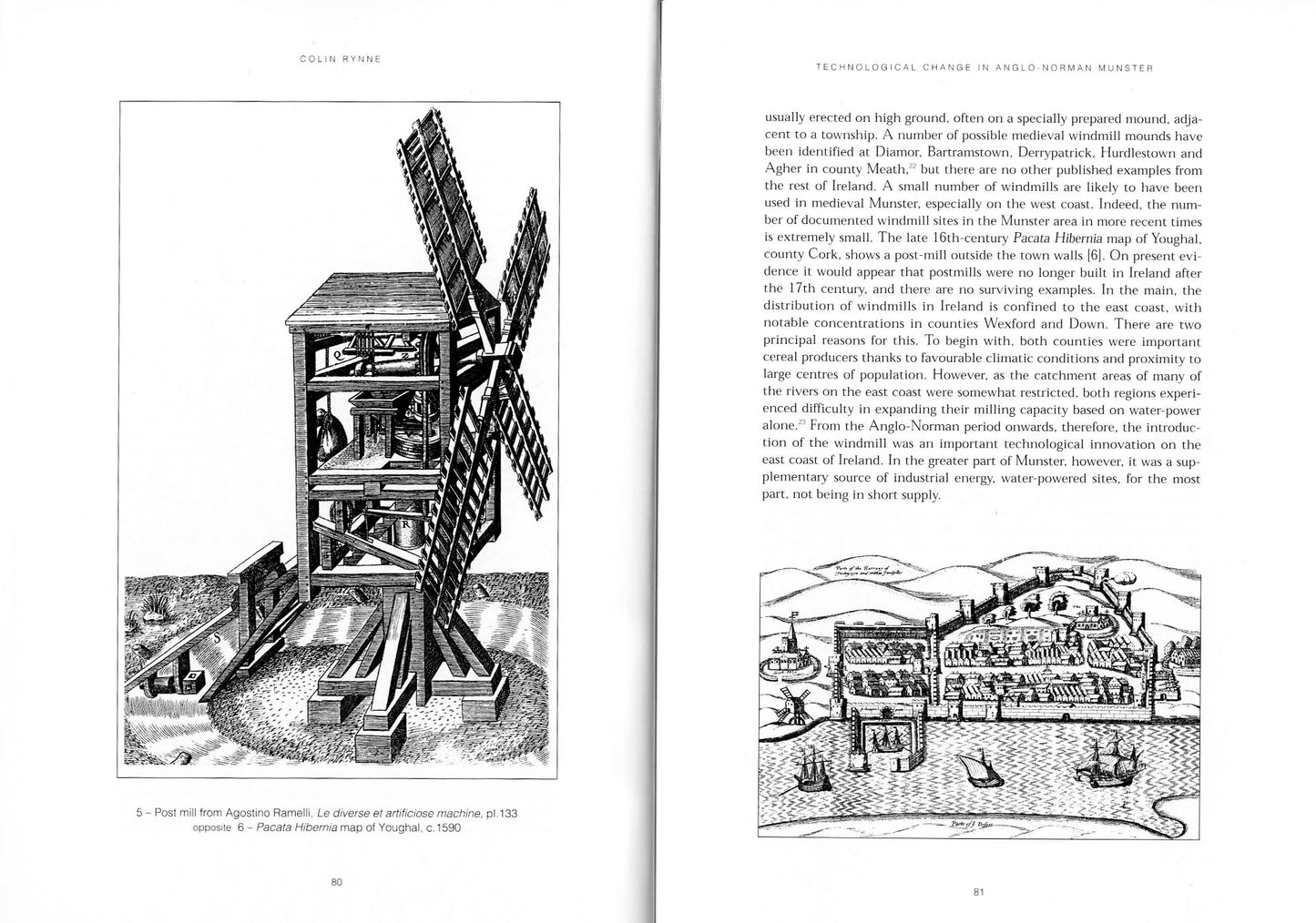

The mill machinery was contained within a wooden framework, and the entire structure was usually erected on high ground, often on a specially prepared mound, adjacent to a township. A number of possible medieval windmill mounds have been identified at Diamor, Bartramstown, Derrypatrick, Hurdlestown and Agher in county Meath, but there are no other published examples from the rest of Ireland. A small number of windmills are likely to have been used in medieval Munster, especially on the west coast. Indeed, the number of documented windmill sites in the Munster area in more recent times is extremely small. The late 16th-century Pacata Hibernia map of Youghal, county Cork, shows a post-mill outside the town walls. On present evidence it would appear that postmills were no longer built in Ireland after the 17th century, and there are no surviving examples.

In the main, the distribution of windmills in Ireland is confined to the east coast, with notable concentrations in counties Wexford and Down. There are two principal reasons for this. To begin with, both counties were important cereal producers thanks to favourable climatic conditions and proximity to large centres of population. However, as the catchment areas of many of the rivers on the east coast were somewhat restricted, both regions experienced difficulty in expanding their milling capacity based on water-power alone. From the Anglo-Norman period onwards, therefore, the introduction of the windmill was an important technological innovation on the east coast of Ireland. In the greater part of Munster, however, it was a supplementary source of industrial energy, water-powered sites, for the most part, not being in short supply."

— Colin Rynne