Gandon

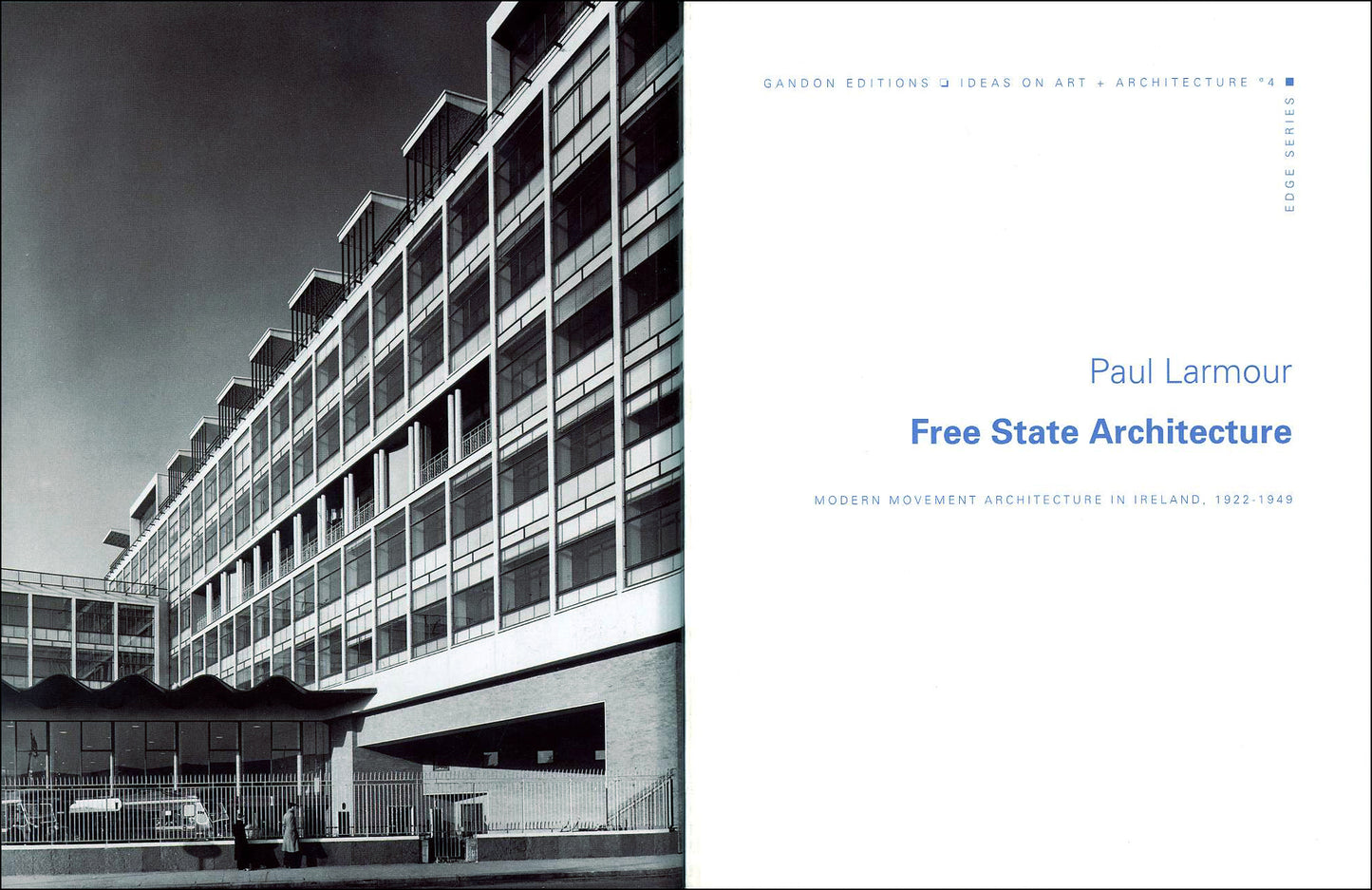

Edge 4 – FREE STATE ARCHITECTURE: The Modern Movement in Ireland, 1922-1949

Edge 4 – FREE STATE ARCHITECTURE: The Modern Movement in Ireland, 1922-1949

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

by Paul Larmour

ISBN 978 0948037 726 112 pages (hardback) 22 x 17 cm 193 illus index

The most vital force in architecture internationally in the twentieth century was the Modern Movement. Born of both newly developing structural techniques and a desire to break from the historic styles of the past, the Modern Movement stood out as encapsulating the essential spirit and energy of modern times. The effects of this international revolution in architectural design and aesthetics can be seen in Ireland from the 1920s onwards, although some of the seeds of change were evident earlier. This new book recounts in detail the formative period of modern architecture in Ireland during the years of the Irish Free State, from its founding in 1922 until the declaration of a republic in 1949.

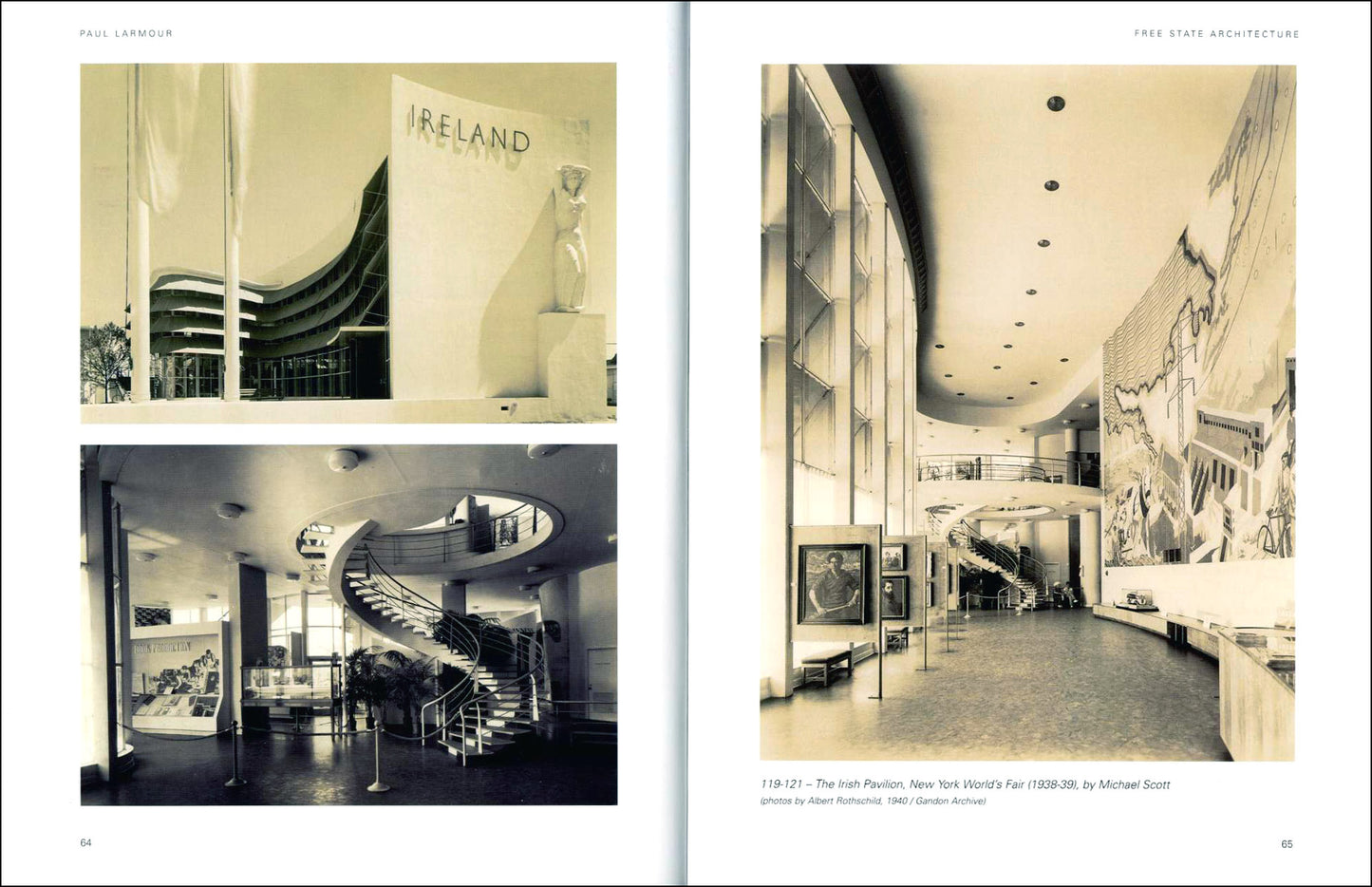

Profusely illustrated using rare archival photographs, original architectural drawings and contemporary sources in the architectural press from Ireland and beyond, this book reveals a rich seam of buildings of unsuspected quality and depth, some of which attracted international acclaim in their time. Such iconic monuments of Irish Modernism as the Shannon Hydroelectric Scheme, the Church of Christ the King in Cork, Dublin Airport, the Irish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, and Busáras in Dublin, are all examined in detail, while a host of other notable buildings and projects are recounted too, from houses and flats, to hospitals, churches, schools and factories, many published for the first time since they were built or proposed.

Free State Architecture is the first book to focus entirely on the Modernist strand in the Irish Free State. With its comprehensive approach, accessible text and fascinating array of illustrations, it makes an original and important contribution to the history of architecture, not only in covering a neglected period in Ireland, but in filling a gap in the story of the spread of the International Style worldwide.

EXTRACT

"Two very notable departures from conventional historicism occurred in Ireland in the mid-to-late 1920s, involving, significantly, imported designs. They were the Shannon hydroelectric power station, with its associated works, at Ardnacrusha, Co Clare (1924-29), designed by the engineering firm Siemens-Schuckert of Berlin, and the Church of Christ the King in Turner’s Cross, Cork (1927-31), designed by Barry Byrne of Chicago. The purpose of the Shannon Scheme, as it was called, was to harness the waters of the River Shannon in the west of Ireland to power a national electric grid and enable the eventual rural electrification of Ireland. It involved the construction of a huge dam and a power station at Ardnacrusha, Co Clare, and a large weir at Parteen some miles upriver. It was a vast and ambitious undertaking for the new Irish government, but one which was to mark an important commercial and political success for it and to greatly enhance the international reputation of the new state. Its architectural form – presumably fashioned by the director of the Siemens’ company’s building department, the architect Hans Hertlein – was equally impressive, with a large steel-framed and concrete-walled power station, reminiscent, in its tall windows, steep pitched roofs, and overall mass, of pre-First World War industrial work in Berlin, such as the AEG factory complex by the pioneering German modernist Peter Behrens. The power station at Ardnacrusha consisted of several parts for quite separate purposes – including transformer rooms, control rooms, switch houses, an oil shop and cooling houses – but interconnected to form a single building. The central part, the generator hall itself, was built up of a massive steel framework, resting on steel hinged bearings mounted on concrete foundations, the spaces between the vertical members of the framework being filled with concrete so that the exterior appearance was of a concrete building. In the original proposal the power station roof was of very low, almost flat profile, while the walls between pillars were intended to be of local rubble stonework. Both of these features were subsequently changed for the executed building, but the ethos of the design remained the same – ‘the construction of the machine house corresponds with the design now usually employed for industrial buildings. Ornaments are avoided and pure utility is the main feature of the buildings.’ Elsewhere, the adjacent structures, such as the sluice and navigation lock buildings, as well as the Parteen Weir buildings, were of even more elemental form, with plain concrete walls and roofs of flat profile. Of particularly imposing and monumental appearance when first erected, rising sheer from dry ground, these more solidly concrete structures still remained impressive in scale even after the essential flooding of the canal and new river bed partly submerged them."

— Paul Larmour