Gandon

CONOR FALLON

CONOR FALLON

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

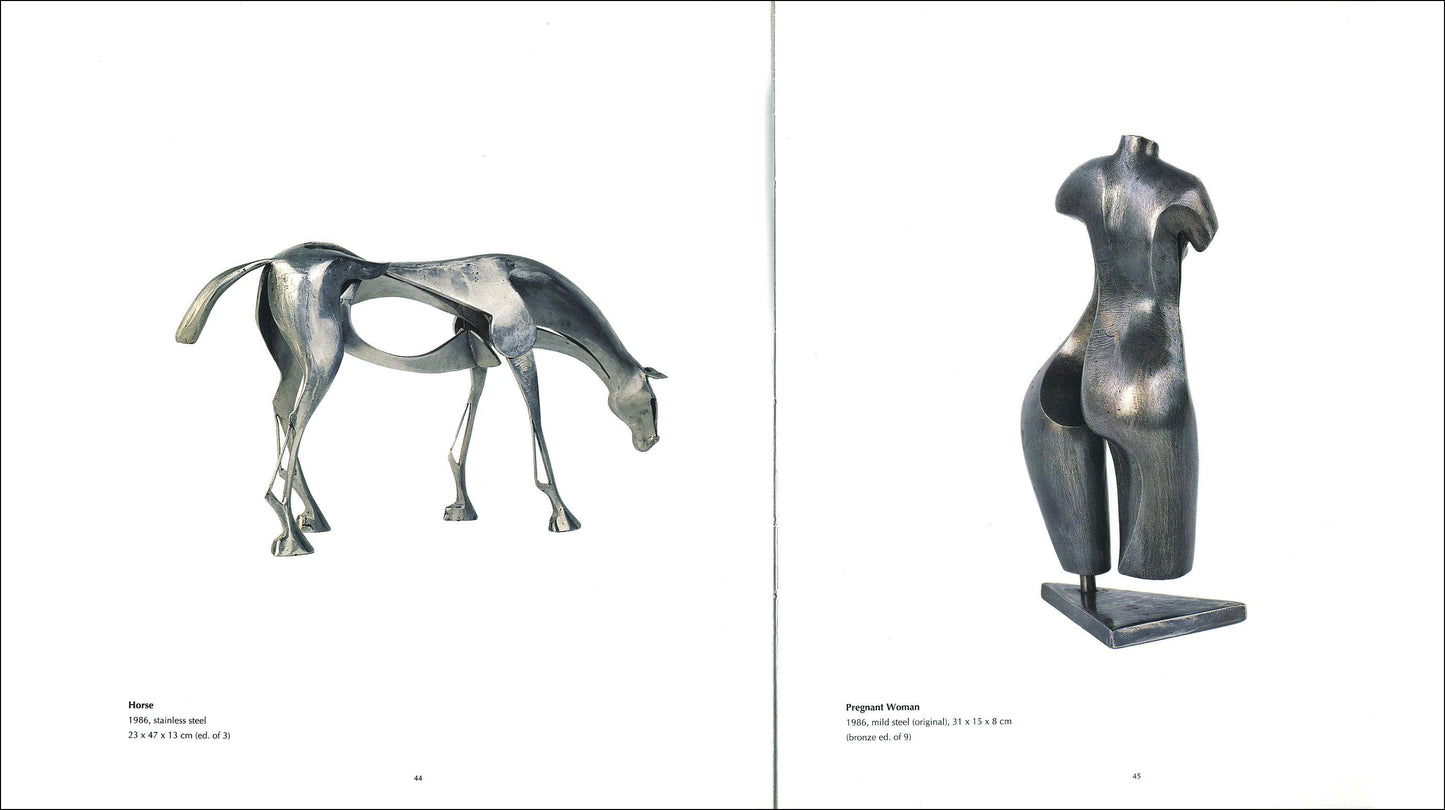

ed. John O’Regan

intro by Séamus Heaney, essay by Hilary Pyle; interview by Vera Ryan; afterword by Ciarán MacGonigal

ISBN 978 0946641 697 72 pages (clothbound hardback) 27x23.5 cm 46 illus

This is the first major study of the work of one of Ireland’s foremost sculptors. Conor Fallon, son of the poet Pádraic Fallon, was born in Dublin in 1939, and grew up in Co Wexford. He was captivated by the natural environment around him, and this led to a dominance of birds, fish and animals in his sculpture. In an in-depth interview with Vera Ryan, he discusses his influences, principal concerns and working methods in making sculpture. There are also lively, intelligent contributions from Séamus Heaney, Hilary Pyle and Ciarán MacGonigal.

Vera Ryan’s essay takes the form of a most remarkable interview with Conor Fallon ... The diversity of four essays leads to a rounded vision of the man, his work, his inspiration, his working methods and influences. The work itself is beautifully photographed.

— Ann Reihill, Irish Arts Review

This book, from the active and resourceful Gandon Editions, has excellent photographs ... and is particularly remarkable for the fascinating interview with the sculptor by Vera Ryan.

— Books Ireland

Irish titles of note are Gandon’s handsome monograph on the sculptor Conor Fallon, with a good cross-section of work illustrated.

— Sunday Tribune 'Books of the Year'

Conor Fallon’s sculptures have the kind of elegant simplicity that’s based on long observation and continual refinement. His (mostly) bird and fish forms have an archetypal inevitability about them. Their uncluttered lines and clarity of form are augmented by clean, clear textures.

— Aidan Dunne, Sunday Tribune

_____

EXTRACTS

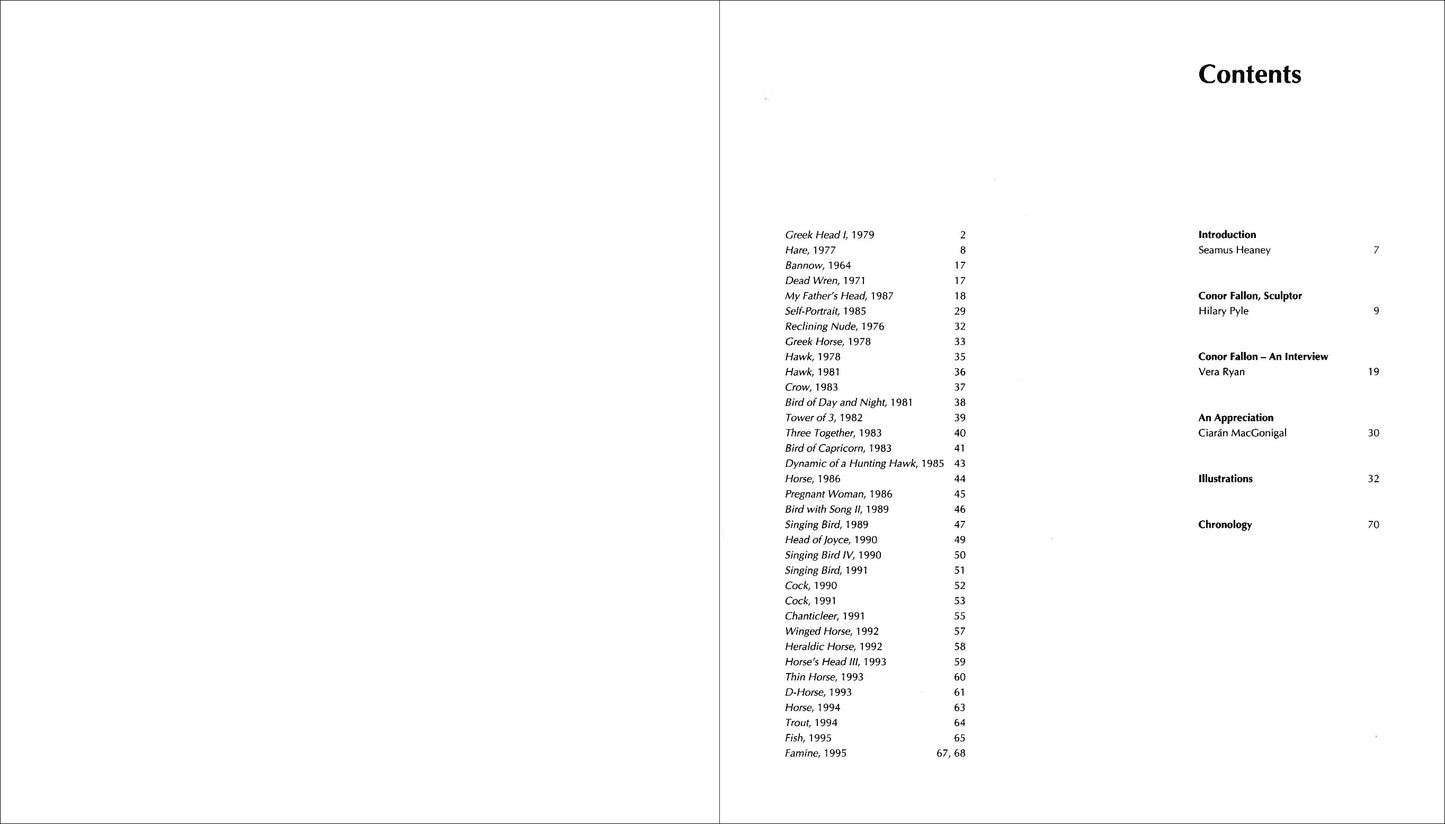

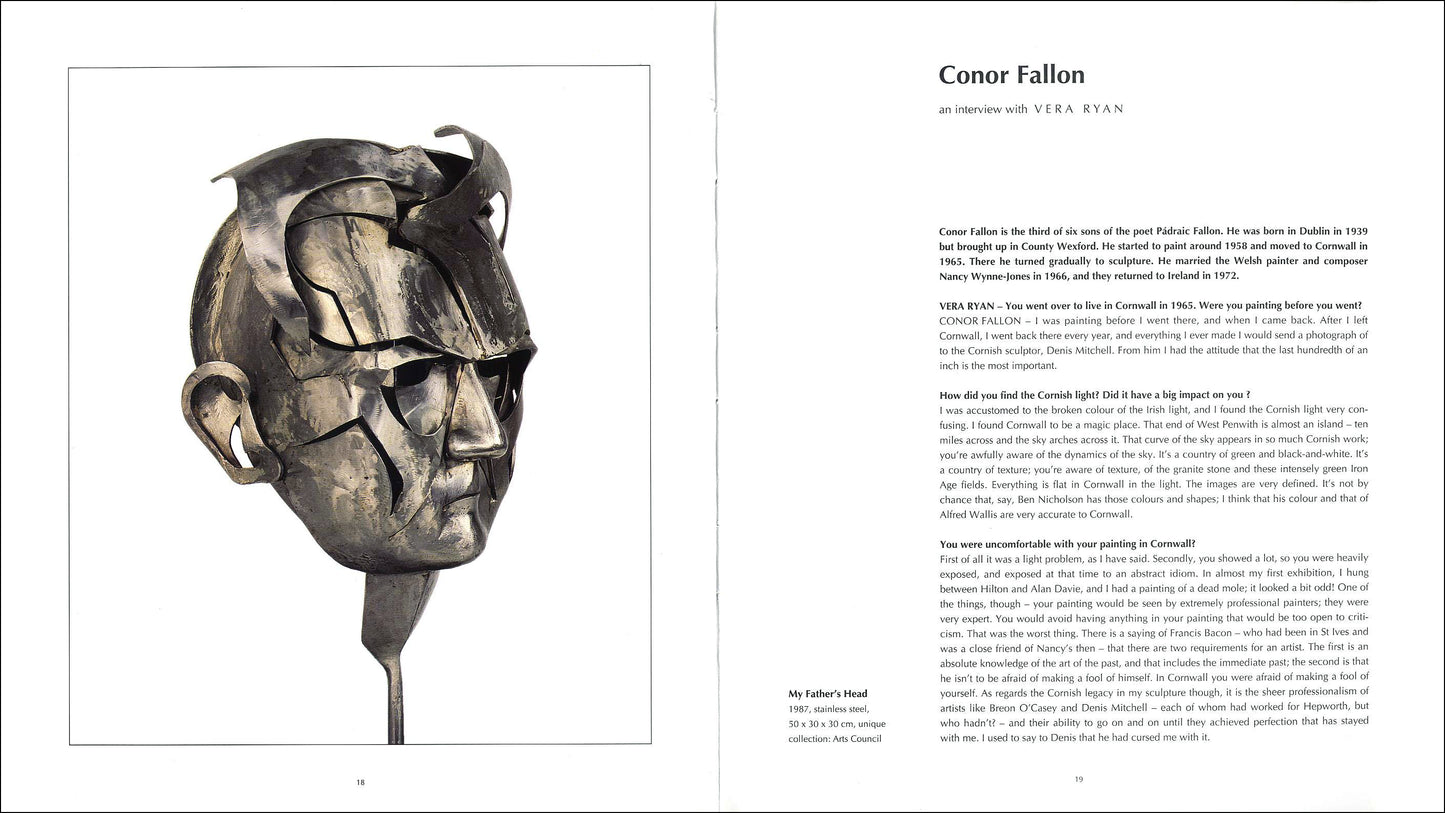

"Conor Fallon has spoken about his way of drawing a natural image until it eventually reaches the ideal form he will reduce to a series of cut-out planes. He acknowledges Brancusi and Calder as models in fining down this practice. However, he never forgets his dependence on the natural prototype which he has absorbed so physically, and this gives his work an authenticity and earthiness which is unusual in one so committed to Cubist principles. It affects his instinctive approach to his medium. His images, instead of being superimposed on the steel sheets, appear to have been pulled out of the metal, itself artificial. The animals and birds he portrays, inhabitants of the countryside in which he himself was reared, preserve their natural characteristics in their transformation, becoming creatures of a twofold creativity. In each work, the artist ponders afresh on the duality of nature and artifice, suggesting that for man, nature and artifice have a common denominator...

The horse has become a significant theme in his repertoire – always a fabulous creature, whether cropping grass in an Irish field or a Pegasus drawn from classical mythology. The animal’s inner space, which is limitless, energises his physical limbs as well as forging a link between the solid planes of its figure and the immeasurability of outer space. His horses may be heraldic, or sinister, as capricious as a dancer or as muscular as a dray, but they are all intrinsically magical. His magnificent stallion in the grounds of University College Dublin is a staggering image, an epitome of the archetype which is at the base of Fallon’s artistic philosophy."

— from the essay by Hilary Pyle

VR – "Did you look at Picasso for a general attitude to art?"

CF – "Yes I did. For the sense of actually emerging from past art and for knowing the history of art, that’s utterly essential. His art is out of his own experience. In relation to women, we’ll say, he had a profound sense of the feminine. So much so that there is an intense awareness of the essential alienation of masculinity from the feminine, the pain of the isolation of masculinity from the feminine. The pain of that isolation is one of the big themes of Picasso’s art. In the Vollard Suite, which I think is superb, the failure that we see in the eyes of the sculptor, and the model’s unawareness of that failure – she absolutely secure in her femininity, he profoundly aware of the isolation of the male from the feminine mystery – is there. I think it’s the mystery. Many of the poems of my father have this reverence for the feminine mystery. The whole thing of the reverence of Picasso for the feminine mystery is in those etchings where she exposes her genitals, in relaxed intimacy, but he isn’t any closer. She is unaware of the mystery. It is absolute anguish. I should think it is the anguish of his life."

"Did Picasso lead you towards self-definition?"

"Yes. From Picasso I believe that I got a reinforcement of the classic; that I am actually a classic artist. It was through his emphasis on the profile, the outer edge of the plane. He hasn’t an emphasis on line, oddly enough. He oozes the whole of classic culture. It is in his bones, it’s without effort."

"Do you think an Irish person can have that sense of the classic?"

"I think we are a classic people. We are a Mediterranean people adrift on a northern sea. Art divides into the Romantic and the Classic. To me, the Classic is out of Egyptian Art into early Greek Art. The kouroi are absolutely supreme sculpture. A lot of Egyptian art is modern; modern minds thought of them. You see with a shock your own sensibility in something four thousand years old, hollowing out behind the face, a device used afterwards by Picasso – and found by Giacometti in his pursuit of the visual – that’s intensely modern. It’s not in the area of naturalism; it is in the area of art. These quiet hieratic kouroi stride through time without any drama. It is the essence of classic. I think the line has been refined so that it isn’t here and there; it is utterly there. It is amazing how hard it is to have that line that is organic and simple. When it’s in neo-classical art, it’s invariably artificial. It has lost either the organic, the sense of the body, or the application of art to the making of the figure. It isn’t aiming at art and it isn’t aiming at nature. It has to be both, without effort. Picasso breathes that. You will find relatively few Picassos that are perfect, in that he avoids a final statement, but the body of his work is supreme."

— Conor Fallon in conversation with Vera Ryan

|

CONTENTS Introduction by Seamus Heaney 7 FEATURED WORKS Greek Head I, 1979 / Hare, 1977 / Bannow, 1964 / Dead Wren, 1971 / My Father’s Head, 1987 / Self-Portrait, 1985 / Reclining Nude, 1976 / Greek Horse, 1978 / Hawk, 1978 / Hawk, 1981 / Crow, 1983 / Bird of Day and Night, 1981 / Tower of 3, 1982 / Three Together, 1983 / Bird of Capricorn, 1983 / Dynamic of a Hunting Hawk, 1985 / Horse, 1986 / Pregnant Woman, 1986 / Bird with Song II, 1989 / Singing Bird, 1989 / Head of Joyce, 1990 / Singing Bird IV, 1990 / Singing Bird, 1991 / Cock, 1990 / Cock, 1991 / Chanticleer, 1991 / Winged Horse, 1992 / Heraldic Horse, 1992 / Horse’s Head III, 1993 / Thin Horse, 1993 / D-Horse, 1993 / Horse, 1994 / Trout, 1994 / Fish, 1995 / Famine, 1995 |