Gandon Editions

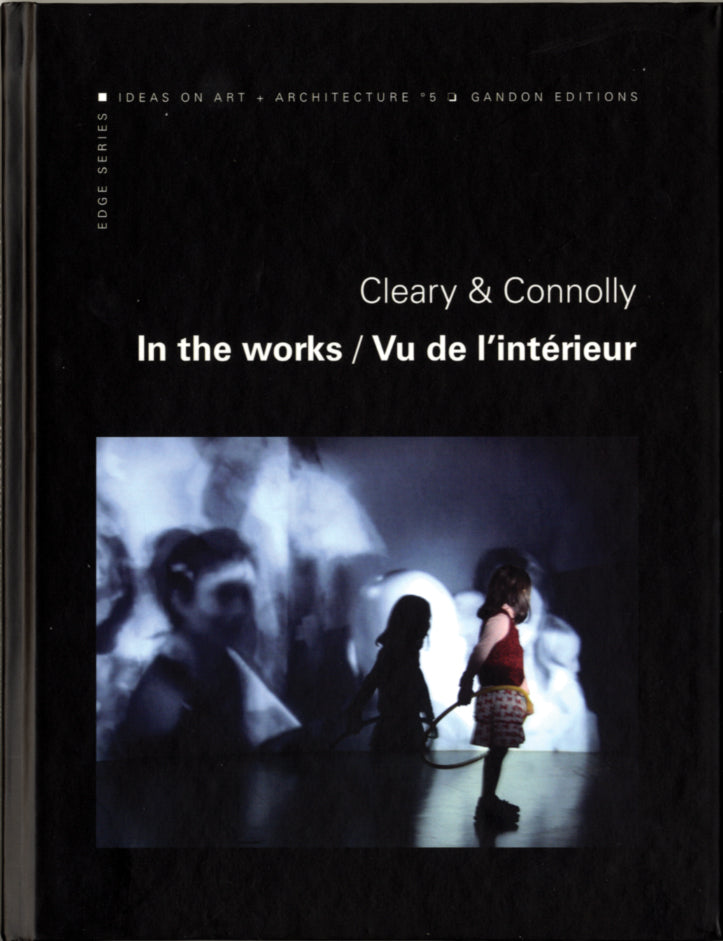

Edge 5 – CLEARY + CONNOLLY: In The Works

Edge 5 – CLEARY + CONNOLLY: In The Works

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

by Anne Cleary + Denis Connolly

essays by the artists, Helen O’Donoghue and Gemma Tipton

ISBN 978 0948037 818 112 pages (hardback) 24x17cm 76 col illus Eng/Fr text DVD

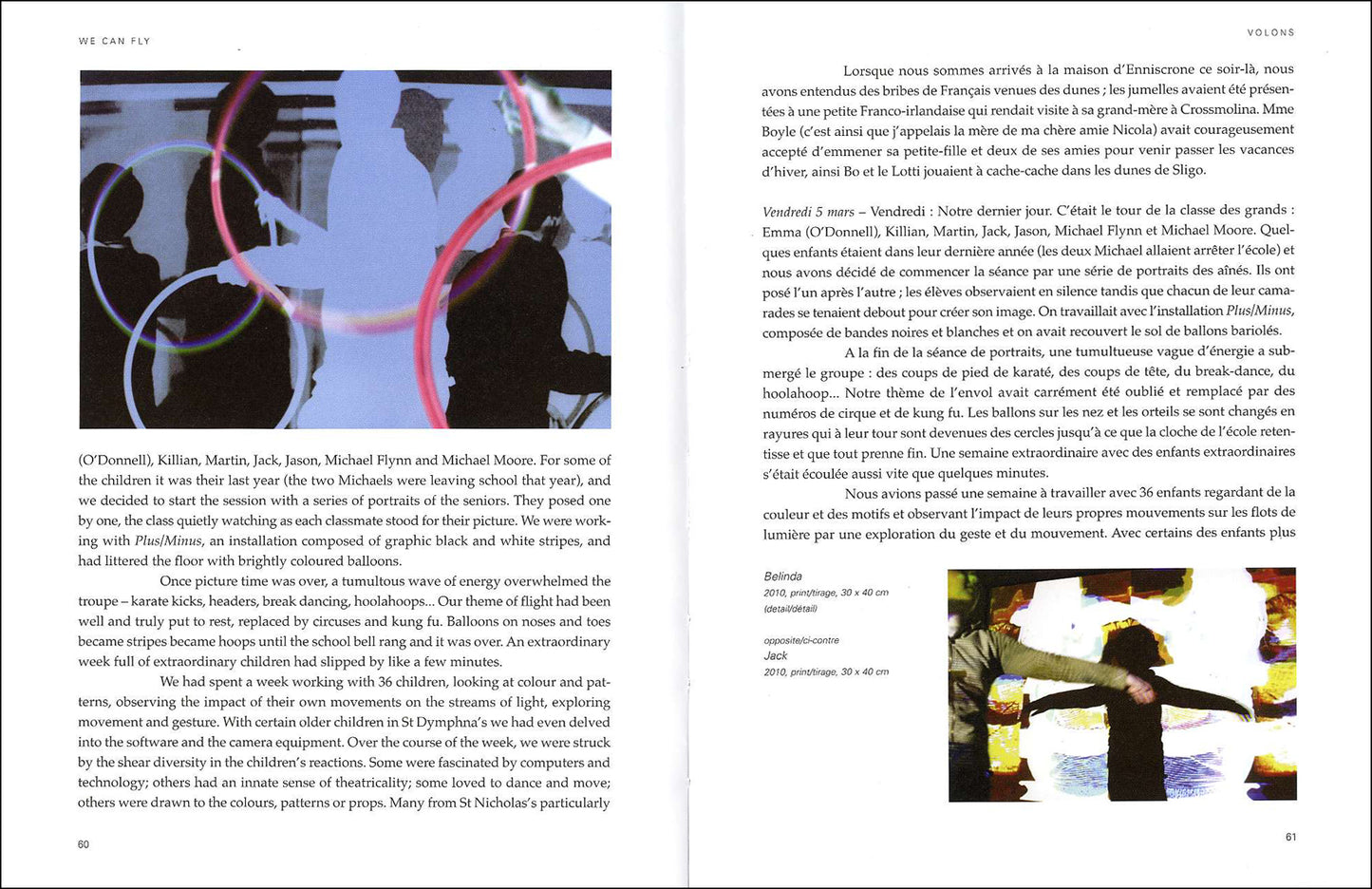

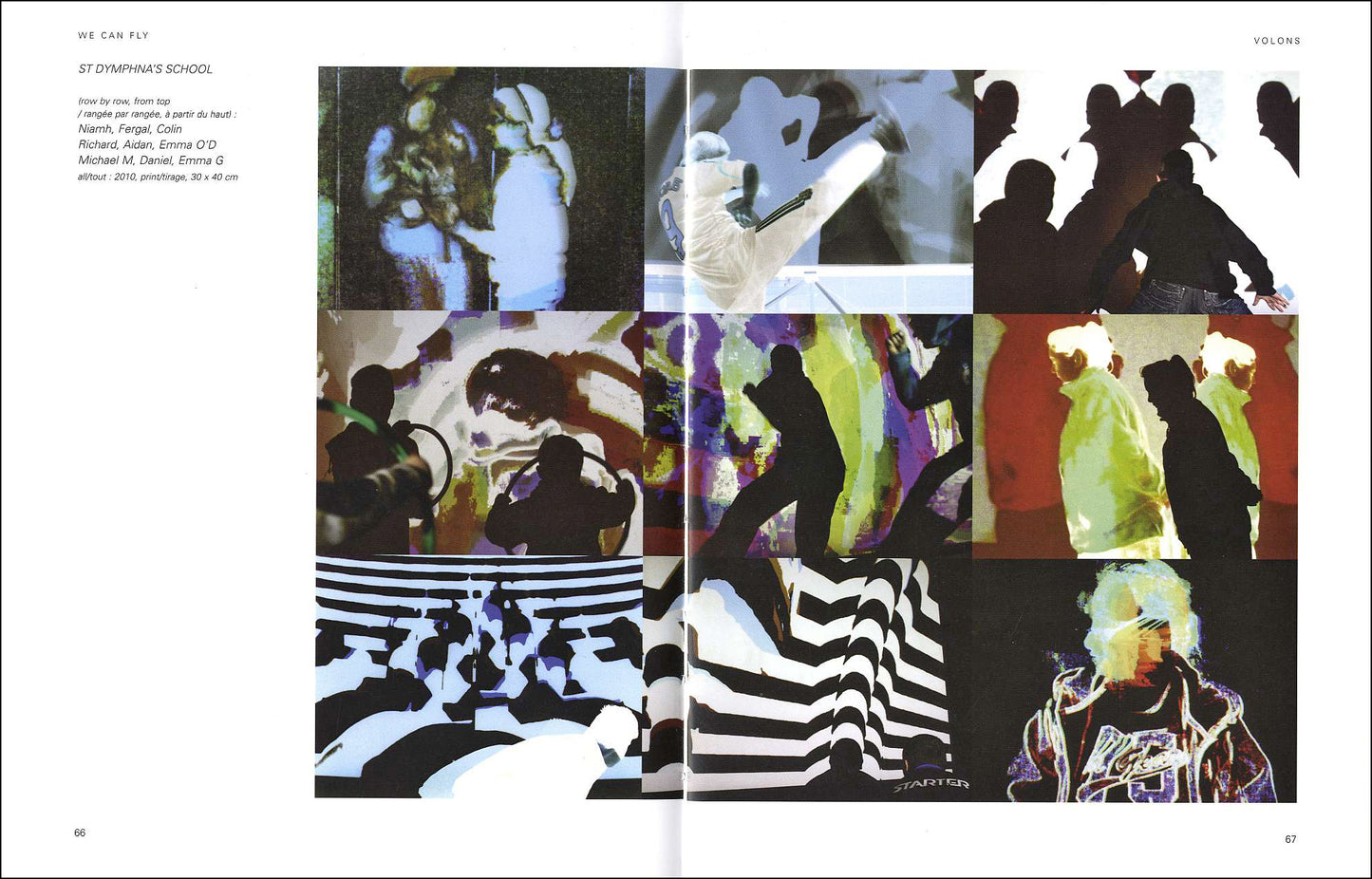

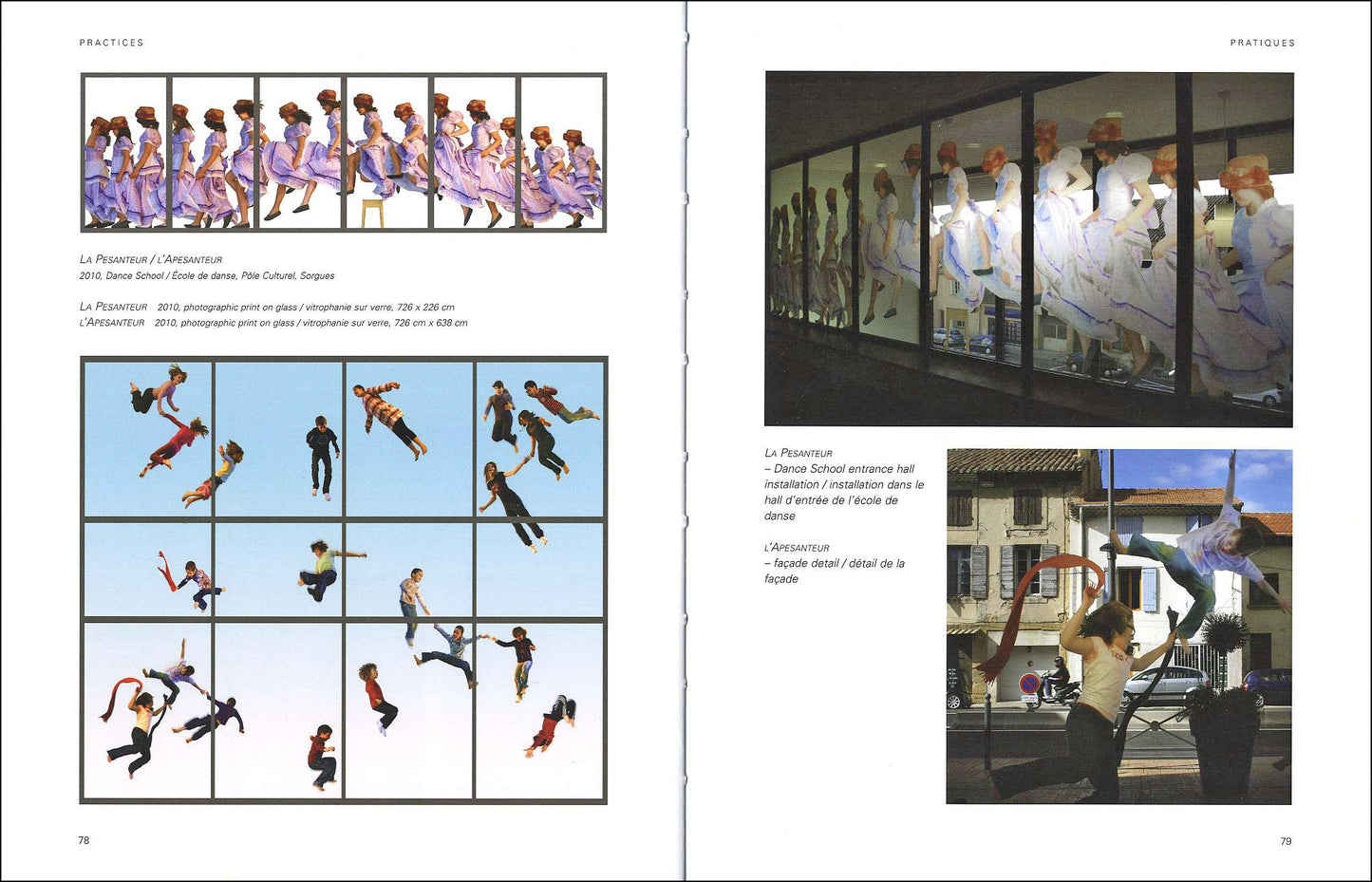

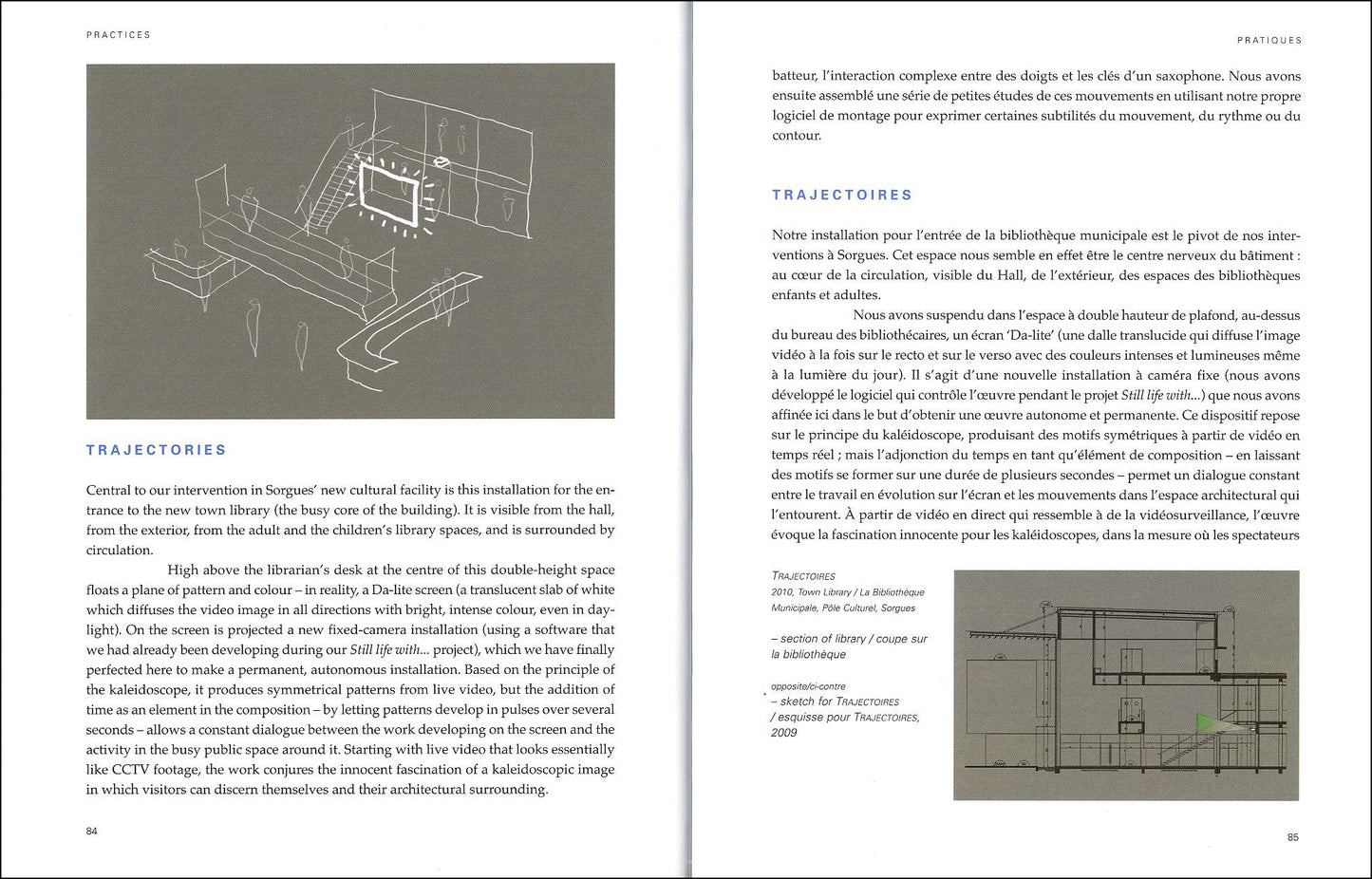

The latest publication from this dynamic duo, the book includes, among other recent projects, their AIB Art Prize-winning installation, In The Works. Artists Anne Cleary and Denis Connolly live and work in Paris, where they moved in 1990 following architectural studies in Dublin. Patterns of behaviour, both in cities and within our institutions, are a central preoccupation of their work, and these they examine through narrative and interactive video, installation, photography and text. In a new monograph on the exceptional work of this collaborative duo, the artists give us insights into the processes of their practice. Written as part-autobiography in journal format, their essays reveal the day-by-day intimacies of their work/lives. They reveal the processes at work from the distinctive perspectives of each of the artists’ practice. Cleary + Connolly’s work is a melody, a fusing of technology and humanity. The age-old need for artists to connect with their audience is Cleary’s main preoccupation, while using new media, the most cutting-edge of technologies is Connolly’s concern. This intertwining is essential in this extraordinary arts’ practice, created by two sensitive people, in order to create magical spaces of the imagination where images will linger long after the encounter.

EXTRACTS

"Maybe children digest visual information better when it’s second-hand, when it has already been partly digested. Maybe we all do. The seventeen seconds a person might spend standing in front of a still life painting may seem derisory when you consider how long it took to paint, but it’s a lot more than the ‘real’ bowl of fruit would get. Our eyes take in visual information all through our waking life, printed into the cones and rods of the retina for a fleeting moments and then passed onto our brains. How important is any of it? Surely that can only be judged by what we do with it. Let’s not forget that all of our ‘new’ media – television, video, cinema and photography – have a common ancestor, as old perhaps as Plato’s cave and not at all unlike it: the camera obscura. People would stand in a dark room looking at a dimly lit upside-down projection of the scene outside the room, mesmerised by the magic of the image even though they may never have stopped to contemplate the scene in its primary manifestation. Domestic animals ignore screens, but human beings, of any age, reserve for them an attention they rarely give to the ‘real’ world. I’ve always puzzled over TV shop displays with camera-to-screen installations. People stop when they recognise themselves, and the world around them, on the television. It may just be narcissism, but if so, why do people never stop in front of a shop window with a mirror inside (except to straighten their hair)?"

— from ‘In the Works’ by Denis Connolly

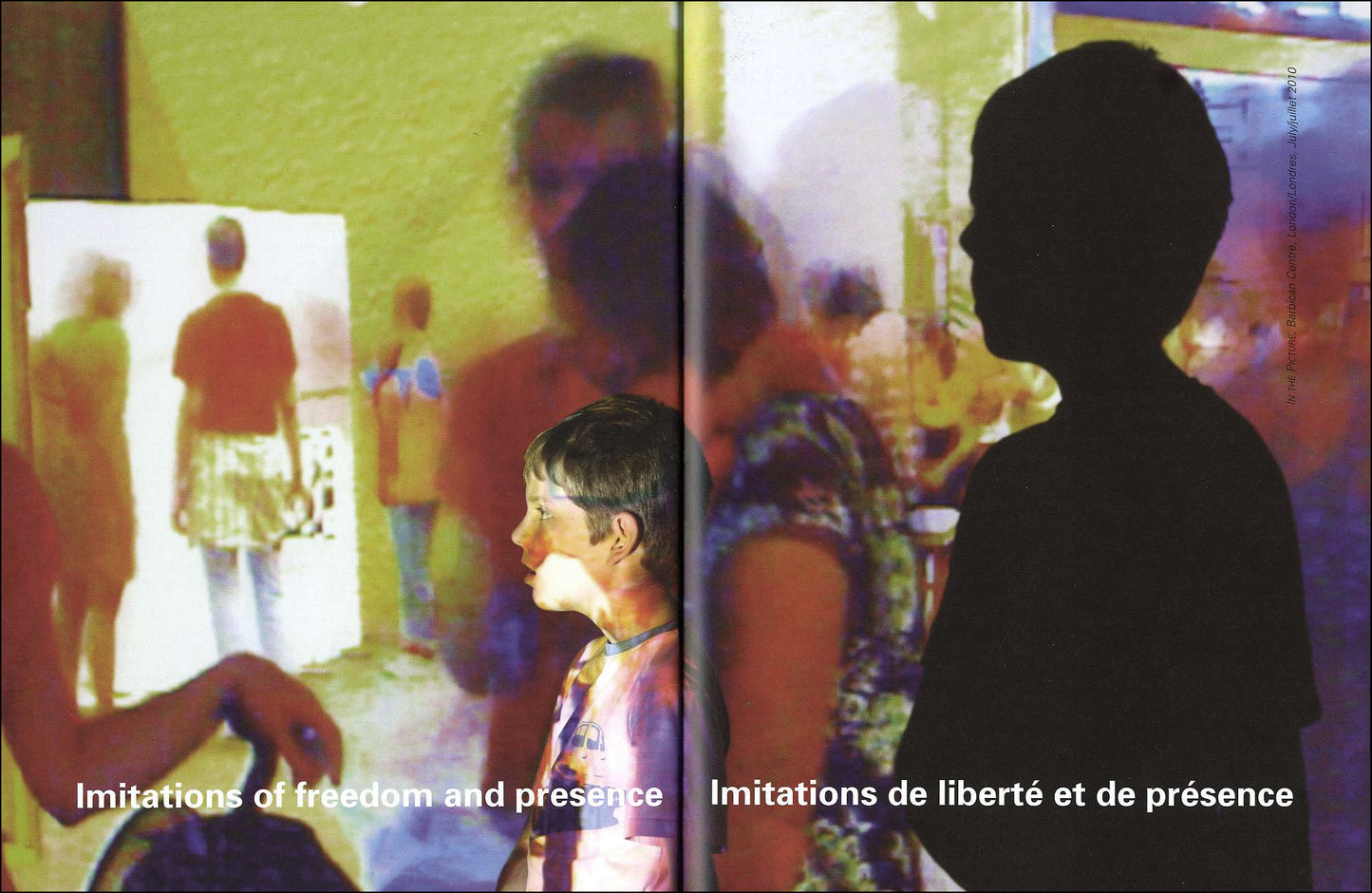

"If art is a mirror, then Still life with... by Cleary & Connolly is an entire hall of mirrors, reflecting and refracting back not only a sense of who we are and how we might appear to others, but also offering the disconcertingly wonderful sense of stepping into the artwork and entering the world beyond the limitations of the frame. This is a subject that endlessly fascinates. Maybe it is because of that tantalising sense that if we can uncover what it is that lies inside or beyond the work of art, deeper mysteries may also be revealed. The Arnolfini Portrait, Las Meninas and 89 Seconds at Alcázar all give a sense that art is something that, with an act of will, we can inhabit as well as imagine, but there is still a barrier, a separation between imagining and being. This boundary is usually reinforced by the single low rope in tasteful muted hue, or maybe a line on the floor, physically marking that cognitive separation in the world’s major museums. But the boundary itself is more than rope or tape; it is made from the accumulations of hundreds of years of art history and prohibition. Don’t get too close, don’t touch, stand still and gaze, and if you must speak, you may only utter the merest whisper. The unreality of art is made even more distant by the unreality of the environment in which we must encounter it. So how can we cross that boundary, and how can we be in an artwork? Cleary & Connolly’s first experimentations in crossing the line to get closer to art came with Touchy (1998). Here the artists’ alter egos traversed the line and broke the rules of engagement with art in sites such as New York’s Metropolitan, Whitney and Guggenheim museums, filming the results. Viewing Touchy gives rise to a strangely uncomfortable feeling, as if something important has been violated. The ultra-polite security guards standing out in black against the white gallery walls warn the protagonists of the dangers of getting too near the art. It could break, be diminished. It is as if, once created, for great art to survive in its greatness, it must become rarefied by separation, removed from the world. Touchy threatens to bring the whole edifice crashing down, so what are we risking by attempting to return art to the world?"

— from the essay by Gemma Tipton

|

CONTENTS Foreword / Préface by Helen O’Donoghue 6-11 |