Gandon Editions

MONUMENT IN THE CITY — Nelson’s Pillar and its aftermath

MONUMENT IN THE CITY — Nelson’s Pillar and its aftermath

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

ed. John O’Regan essays by Patrick Henchy, Shane O’Toole, Raymund Ryan

ISBN 978 0946846 153 72pp (pb) 30 x 17 cm 60 illus

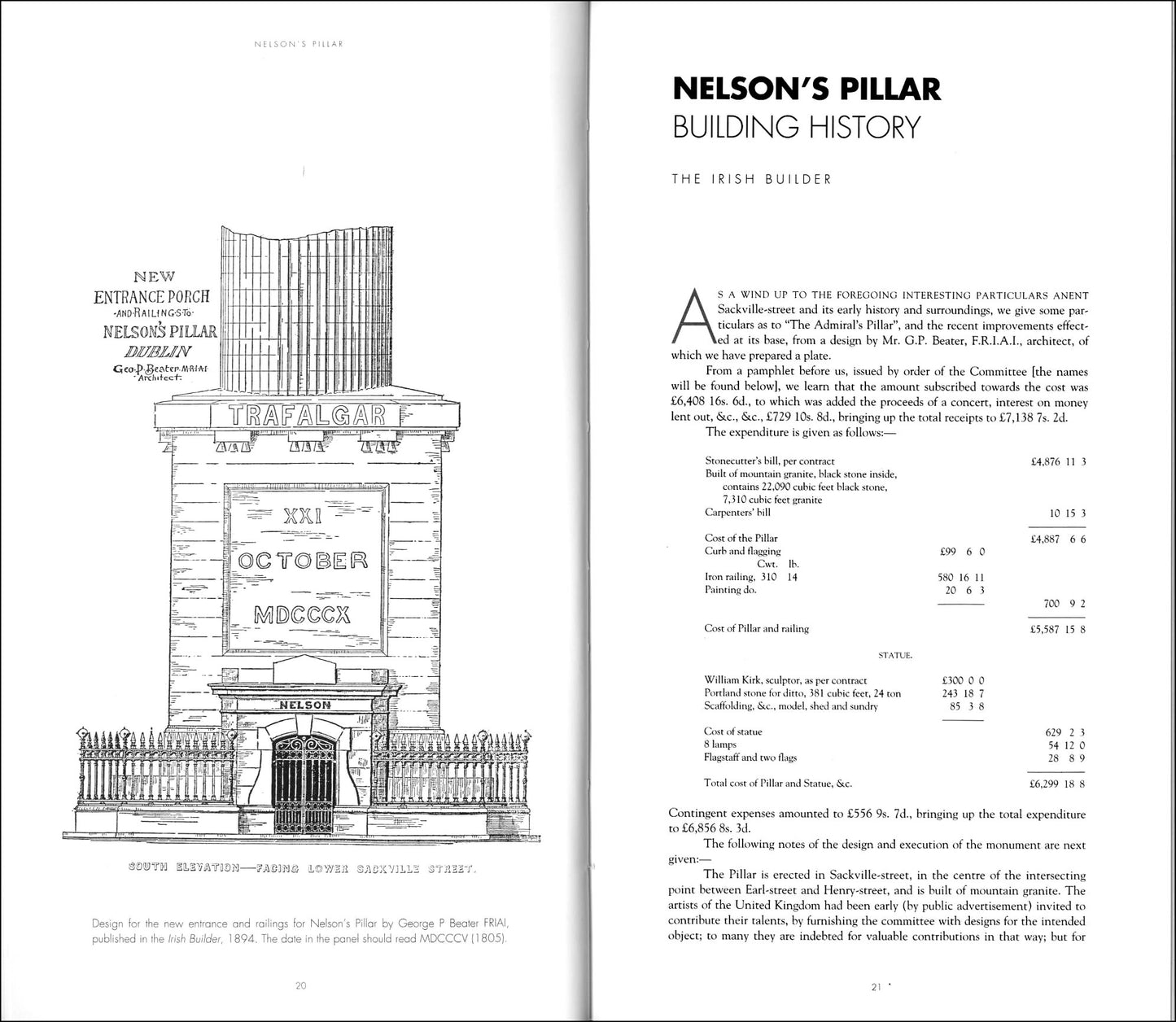

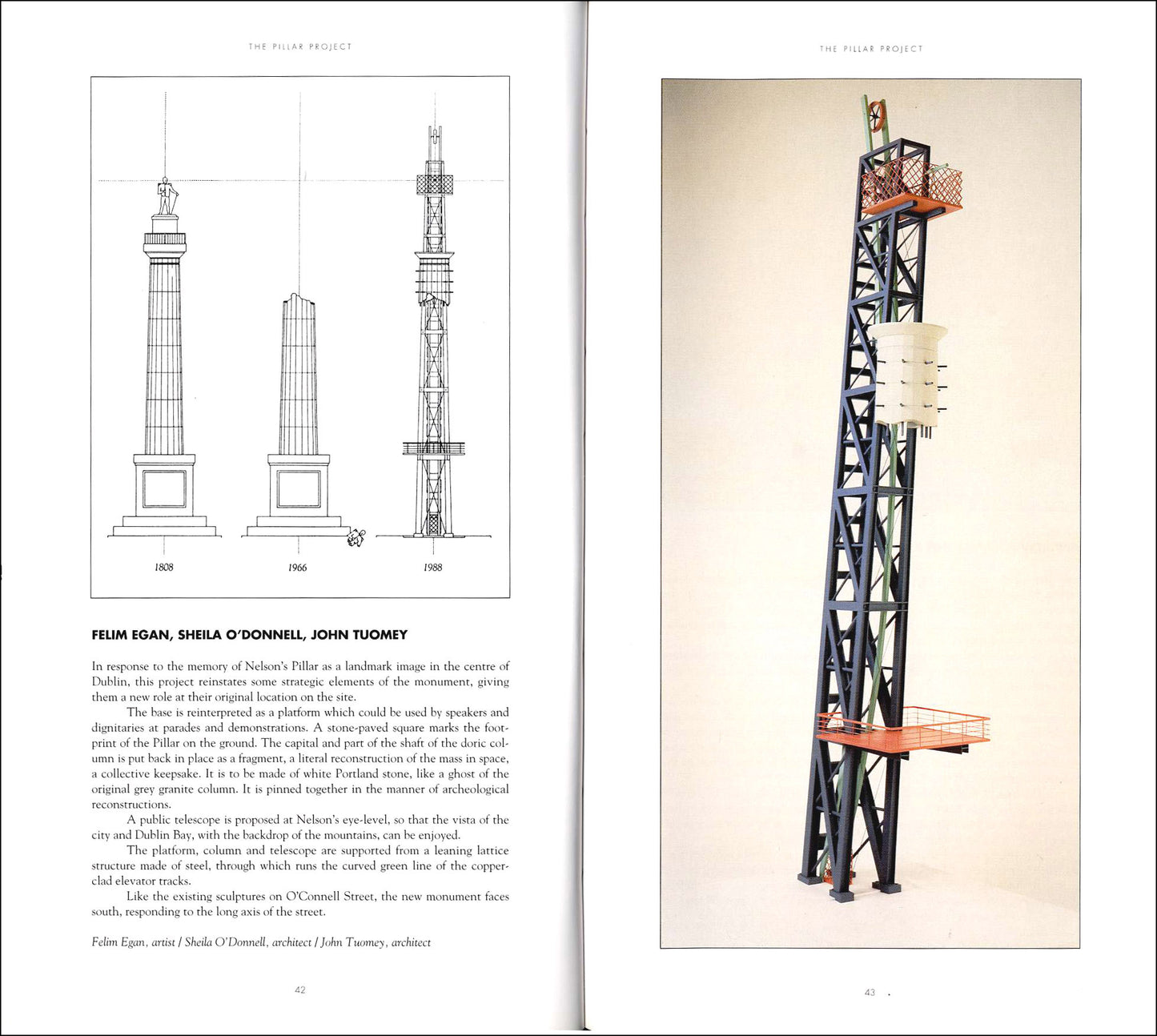

The launch of an international architectural competition for ideas and proposals for a new monument on the Nelson Pillar site in Dublin – for so long the symbol for Dublin – prompted the publication of this book. Brought together here is a detailed history of Nelson’s Pillar, a reprise of the Pillar Project (the 1988 counter-project by 50 architects and artists), and a keynote essay by Raymund Ryan exploring the history and potential of the monument in the city.

EXTRACTS

"In 1988, the Pillar Project brought together fifty architects and artists, and asked them to make suggestions for a replacement for ‘The Pillar’, Dublin’s outstanding landmark and symbol until it was blown up in 1966. The theme of the project – the monument in the city – is of universal relevance ... Among its objectives, the project sought to make proposals for a new symbol for Dublin (such as the Eiffel Tower is for Paris, or the Statue of Liberty for New York); to stimulate and contribute to an informed public debate regarding the enhancement of O’Connell Street, the main street of the nation; and to establish networks for the future by providing a unique experimental opportunity for architects and artists to work together on the conceptual development of an urban project of significant scale."

— from the introduction by Shane O’Toole

"Today’s designers are uncomfortable with the issue of monumentality. Some positively loathe the idea – these include many still within the strict Modernist camp – others have come through several decades of Postmodernism to witness their experiments with formalism and eclecticism degenerate towards kitsch. The artist Jeff Koons is in this sense a perfect representative of our global market economy. Monuments can certainly influence the image and development of a particular location, but today monumentality is not easily isolated from other aspects of a rapidly changing environment. Society – especially, perhaps, when conscious of change – has a great hankering for communal symbols. These symbols may be as ephemeral as a soap opera and the flowers left at Kensington Palace after Princess Diana’s death. Or they can be as lasting as the Giza Pyramids, the Pantheon and the Eiffel Tower. But only these latter symbols fit the precise definition of the word ‘monument’. According to the Chambers 20th Century Dictionary, a ‘monument’ is ‘anything that preserves the memory of a person or an event … any structure, natural or artificial, considered as an object of beauty or of interest as a relic of the past: a historic document or record’. A monument, therefore, is a mnemonic device, an aide memoire. It cannot be mute – it must refer to something. A monument need not be architectural. It might be landscape, as with memorial gardens, or the six million trees planted in Israel, but it is concerned with time. Monuments can be pre-planned, as with the tombs of popes and kings, or they can evolve over time, as happened to Eiffel’s tower (originally a communications structure for the Paris Exhibition but now a monument to French modernité). Of course, contemporary proposals do not always meet with universal approbation. The ideals of classical civilisation, embodied in purist geometry and the human form, have to contend with an often arbitrary sentimentalisation. If monuments are to be built today, is the language of their construction one of critical engagement or of the least offence? What do we intend to commemorate?"

— from the essay by Raymund Ryan

|

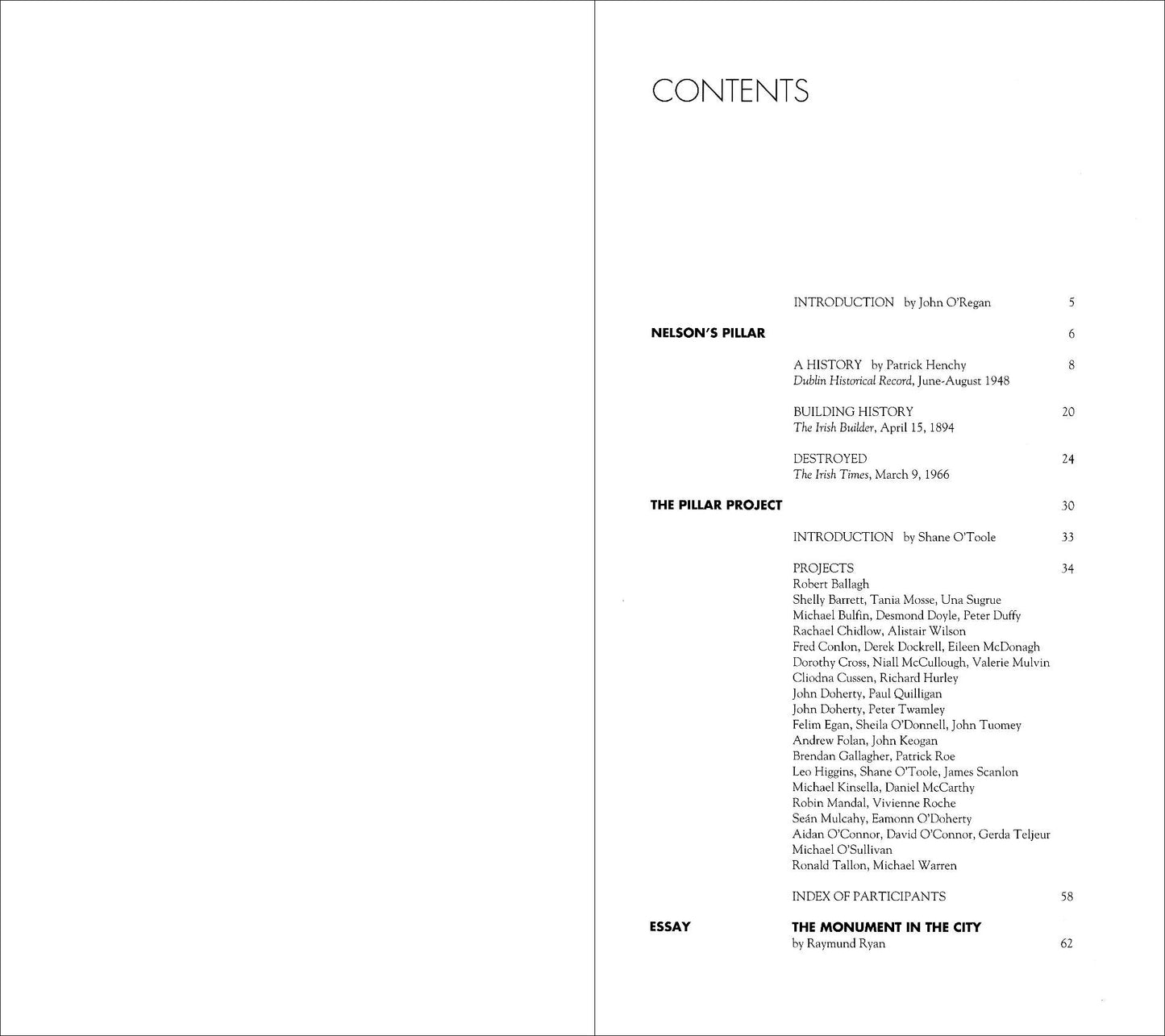

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by John O’Regan 5 PROJECTS 34-57 Index of Participants 58 |